It’s minor in the scheme of the genuine pain and suffering that will likely result from the results of the 2024 U.S. presidential election, but it’s nonetheless notable in this popular-culture context: Donald Trump’s victory on Tuesday made me actively dread this week’s episode of a show that, under normal circumstances, I happily anticipate like an easy-to-please 12-year-old in 1992. The same thing happened in 2016, of course, with this TV show and, to my recollection, no other; mostly, good TV (or maybe especially mediocre or bad TV) helps temporarily numb the shock and stomach-churn of a current event. Thinking about my all-time favorite shows, it’s hard to imagine imagine an election, no matter how seemingly catastrophic, causing genuine, specific trepidation about watching a new weekly installment of Freaks & Geeks, Seinfeld, or even something more nominally contemporary in its angst (at the time, anyway), like Girls.

Saturday Night Live, meanwhile, is uniquely positioned to make its own newsworthy hay of current events – and also its own cringeworthy hell when those events don’t seem particularly compatible with cheap laughs. It’s an extreme example of how the political and satirical worlds have shifted over the past few decades – the most extreme example of how the normie reaction of “can’t wait to see this on SNL!” – sometimes on weeks or even seasons when the show isn’t airing – has flipped into (some) fans’ fervent hope that the show will hit literally anything else. Or that it would just disappear the weekend after a major national screw-up. Hardcore Last Week Tonight fans don’t feel that way, do they?

Regardless, these are the unfortunate circumstances that might lead someone to, say, not even hate that admittedly shudder-inducing McKinnon-as-Clinton dead-serious “Hallelujah” opening from the post-election episode in 2016. Anyone could name the reasons this didn’t work, and I wouldn’t disagree; I’d only say that I felt a kind of relief (albeit temporary) that it wasn’t some dumb sketch about Trump putting gold toilets in the White House – that anyone at the show might admit that, actually, they were feeling pretty shitty, too.

Of course, it’s hard to play that same note again, especially without a McKinnon figure in the cast who might be assumed to have some leeway with the audience. (Even setting aside the poor reputation that opening has now, the show already spoofed its own self-seriousness later that same season anyway.) Instead, the show opted for something similarly direct, but with actual jokes: A portion of the cast appearing as themselves, performing fake groveling about how much they’ve always been Trump fans and will support him all the way. The sarcasm directed at Trump and Elon Musk (capably impersonated by a still-lingering Dana Carvey) didn’t quite land; without the mask of an impression-driven sketch, it’s easier to think about how, hey, actually, this show did some real-life groveling toward both of these guys when they each appeared as welcomed guests. The knowing laughs about how everyone really feels don’t quite materialize, even if one can’t really blame Ego Nwodim, Bowen Yang, or Sarah Sherman, et. al, for their employer’s decisions (some of which were made before some of these cast members were even working there).

The cold open, which usually doesn’t warrant this much discussion, pointed to a broader shift in how the show would deal with the latest election disaster: Not quite ignoring it, but not quite mustering the vigor to mount some perceived comic counter-attack or find some unexpected angle. That was certainly the tone of host Bill Burr’s monologue, which fake-pivoted away from politics to “keeping it light,” then pivoted back to some election material that felt terribly outdated, as much of it would have even a month or two ago, then moved away from the topic once more. It felt like a whole lot of maneuvering, considering Burr seemed to have been booked as the Dave Chappelle Emeritus, a blunt-spoken comic willing to speak some possibly-uncomfortable truths, regardless of election results. If that was really the reason he was there, it doesn’t seem like anyone told him. (Or maybe he had a different set of expectations, having previously hosted in the run-up to the 2020 contest.)

The rest of the show did and did not ease that general queasiness. Weekend Update had one of its funnier outings in a while; Michael Che’s over-it, checked-out vibe is perversely funnier when he’s addressing potentially lasting damage to the country, glass in hand, because it forces him to appear to kinda-sorta care about something, albeit in a disaffected way. (Disaffection has long been a go-to Update anchor strategy, but later-period Che can’t always make it work for him, because he’s surely free to leave after a decade at the desk.) Not exactly catharsis, not exactly a slog.

Apart from a mention here or there, the rest of the sketches – twice as many live pieces as last week, and as the similarly sketch-light first outing from Burr – ignored politics, largely for the best. What was most fun about this weird assortment of sketches was the range of formats, perhaps cooked up as a series of distractions: No talk shows, no game shows, and some concepts that were genuinely ambitious in their logistics, like the sketch about two guys calling their emotionally repressed dads. It didn’t reveal much about those relationships, nor was the live integration of two different split-screen phone calls all that graceful, yet there was something unexpectedly sweet and observational about it, despite and/or because of its refusal to get into election-season divides that often form between parent and child. (Maybe they’re still figuring out a way into the idea that Gen Z harbors more Trump supporters than many thought possible.)

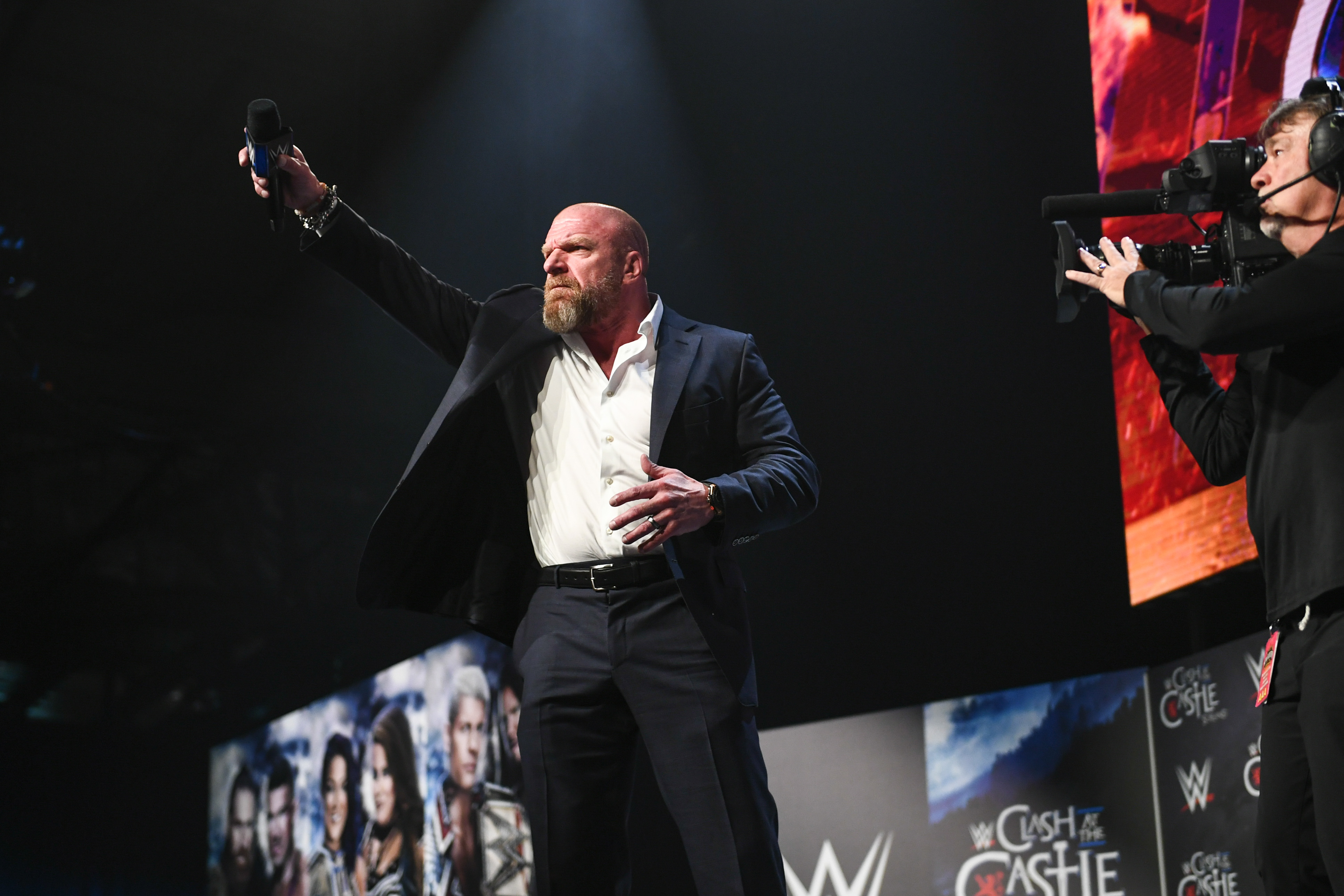

Look, too, at that odd little musical number about bald men, and how it was set up by Mikey Day and Sarah Sherman playing a couple on a date, musing that nothing odd had happened with each other or the waiters – all but underlining the shticky out-to-eat set-ups of so many SNL sketches (including one that aired about 10 minutes later!), and nonetheless introducing the litany of singing bald men who made up the rest of the restaurant setting. It was all oddly wholesome, especially with a self-styled agent of abrasion like Burr in the mix.

Is that enough to work as an agreeable distraction from something the show itself must bring up as soon as it starts? I don’t know; is anything? SNL in 2024 isn’t exactly occupying the cutting edge of topical humor – and isn’t exactly offering pure sketch-comedy comfort food, either, given its oft-refreshing lack of a “main” star or endlessly repeated catchphrases. This week, it was put in the awkward position of trying to be both of those things regardless. As a reflection of the post-election blues somewhere around half the country must be feeling at the moment, it works surprisingly well: In the midst of shock or depression, here are two disparate assignments you didn’t ask for that nonetheless must be completed on some level, possibly while wondering what you could have done to avoid this situation entirely. In this impossible realm, the show did a better job than many.

What was on

Besides the two aforementioned sketches, the inkblot sketch with Burr as a fireman who can see disturbingly detailed cartoon-character fan art and the father-son discussion about Snake Skin, the latest Andrew Dismukes/James Austin Johnson musical collaboration both made good use of Burr’s plainspoken persona. Neither of them really got to the next level from their inspired premises, but again, points for structural variety: the inkblot bit used actual illustrations to show exactly what Burr was seeing, and the Snake Skin bit cut between “normal” dialogue and remnants of an old-fashioned call-now ad for the band’s greatest hits.

What was off

I have some affection for watching a sketch just outright bomb, and while the support-group bit with Bowen Yang throwing a fit over his seemingly surmountable problems (malfunctioning Tubi account; faltering cell battery) hauled out some absurd laughs in the clutch, it also featured the one-two punch of a few laugh lines getting absolutely zero audience response, and a couple of cast members nearly cracking up anyway. By comparison, Ashley Padilla’s showcase (?) as a wife who can’t write a joke about four beautiful dogs, no matter how hard she tries, seemed downright innovative, even though it didn’t really “work” in the conventional sense.

Most valuable player (who may not be ready for prime time)

This felt like even more of a team effort than usual, but the variety of sketches did show off the stealth versatility of Andrew Dismukes, who’s not exactly a chameleon, but managed to play pretty different roles tonight. Plus, whenever he does songs with James Austin Johnson, I’m delighted.

Next time

It’s been repeatedly over 70 degrees in New York City, so why can’t Charli XCX give us one last gasp of brat summer?

Stray observations

- • I have complicated feelings about Dana Carvey, but it is objectively kind of cute and amusing that the show’s big 50th-anniversary celebration could really just amount to “Carvey is a cast member again.” Yeah, Maya Rudolph and Andy Samberg have been there, but they seem unlikely to make a big return, whereas Carvey is ready to pivot to a new impression that no one else in the cast has really nailed.

- • This was literally the first time I’d ever heard or heard of Mk.gee, and if you asked me how I thought a musical act called and pronounced that would sound, “like the bridge to a Police song” is not where I would have landed.

- • At this point, it’s been years and I’m still not sure how I feel about whatever writers’ predilection for a completely off-season movie spoof. On one hand, I appreciate the flagrant rejection of topicality that must come with dedicating an elaborate filmed piece to spoofing Good Will Hunting. But there’s no rule that says really, really wanting to spoof Good Will Hunting can’t also feel a little stale.

- • Take care of yourselves, everyone.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·