Although “All We Imagine as Light” was not selected by India as its nominee for Best International Feature Film, the indie from India has broken through to find acclaim and an arthouse audience here in the U.S. The contributors to Film Comment recently named it as the Best Film of 2024, while IndieWire’s survey of 177 critics had the film at number four on its list. And, on Sunday night, director Payal Kapadia was nominated for Best Director at the Golden Globes, alongside the directors of Oscar favorites like “Anora,” “The Brutalist,” “Conclave,” “Emilia Pérez,” and “The Substance.”

The story of the lives of two nurses living in Mumbai is filled with quiet, intimate vignettes of the everyday life in Mumbai, but it is also brimming with exciting cinematic poetry that brings to life their emotional lives. While Kapadia was on IndieWire’s Filmmaker Toolkit podcast, the director broke down how she used the camera, sound, editing, color, and light to turn her characters’ ordinary lives into an extraordinary piece of filmmaking.

A City Symphony of Voices

Before we meet Prabha (Kani Kusruti) and Anu (Divya Prabha), Kapadia introduces us to their city. In the film’s opening sequence, we see glimpses of Mumbai in flux and transit — a pre-dawn market being broken down, commuters on the train to work — while hearing snippets of voices of ordinary people who live in the city. The opening sequence is the perfect preface to meeting Prabha — at the end of it, the camera lingers on the protagonist, who is presented as just another of the thousands of commuters — but it is also a window into the director’s artistic process and use of form.

While writing the script for “All We Imagine as Light,” Kapadia and cinematographer Ranabir Das (the director’s partner in life and filmmaking) interviewed people about their lives in Mumbai. What began as a way of gathering source material and inspiration for her script evolved into something more.

“We felt like somewhere we wanted to remember those voices that we had met, so we did it again with more purposefulness,” explained Kapadia, who re-conducted the interviews, no longer using rudimentary phone recordings. The director had been inspired by István Szabó’s 1977 film about Budapest, “City Map.” “It’s a lovely little film that uses voices in this way, you never see the people, but you just hear these very intimate, very moving voices, and I wanted to do that for Mumbai as well,” she said. “We wanted to do a documentary sequence in the beginning, and we felt that it was like a city symphony where there are many, many voices.”

While Kapadia’s first feature “A Night of Knowing Nothing” was a “documentary,” “All We Imagine as Light,” she still views her first scripted feature film as a continuation of her practice. “I like very much this juxtaposition [of fiction and nonfiction filmmaking],” said Kapadia. “I feel that when the nonfiction and fiction sit together, it makes the fiction, for me, more realistic, and it has this quality of perhaps another kind of truth to it.”

Stolen Moments: The Freedom of Night

The opening captures the director’s love/hate fascination with her hometown, which is at the heart of the film’s story and use of form. In Mumbai, Kapadia explained, most are forced to live far from their work, and often their friends and family as well. So much of Prabha’s time is taken up by her job and commute.

“You have no time for yourself. You’re just coming home, you just need to make your food and eat it and go to sleep, or wash your clothes for the next day, many can’t get weekends off,” said Kapadia, who intentionally shot the Mumbai section of the film during monsoon season, so the audience could visually feel the weight of everyday life in the city. “Sometimes in Hindi movies you have these song sequences where the monsoon is supposed to be, oh, so lovely — it rains and the lovers can run around … but the truth of the monsoon is that by the time it’s July it’s raining three to four days continuously, torrential rain, the streets get flooded, the trains stop, you get stranded somewhere. It’s a pretty low-lying city, so it’s really difficult to get to work.”

There is also a great deal Kapadia loves about Mumbai. On a practical level, there’s work and it’s relatively safe for women to get around compared to other parts of India. There’s also an energy and a sense of a constantly changing city (although, as the film explores, not always for the best). For both the filmmaker and her young protagonist-in-love, this aspect of city, both narratively and cinematically, is best captured at night — the one brief part of the day Anu can sneak out to meet with her forbidden lover Shiaz (Hridhu Haroon).

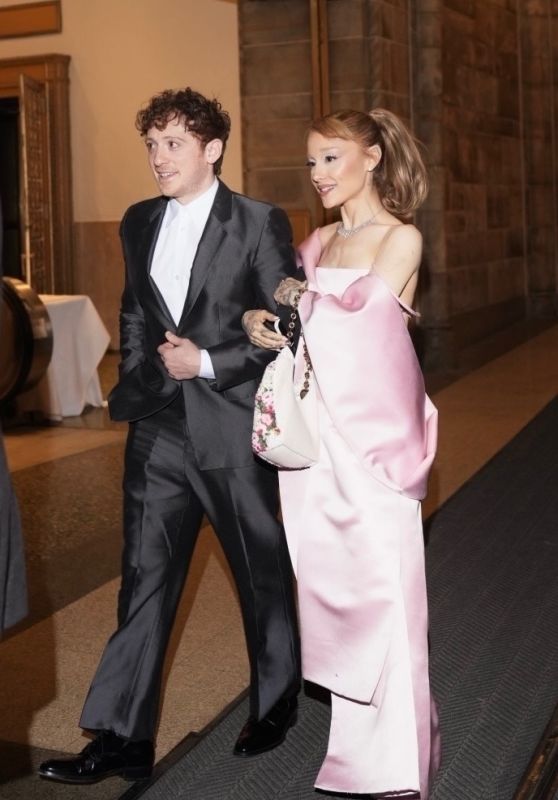

‘All We Imagine as Light’Janus FIlms/Courtesy Everett Collection

‘All We Imagine as Light’Janus FIlms/Courtesy Everett Collection“I’m very attracted to the nights in Mumbai,” said Kapadia. “I felt that the evening was probably when these two could actually meet and be a bit more anonymous and hide in the dark corners of the city.”

The wetness of the city becomes electric and blue under the city lights at night, the perfect backdrop for the young lovers trying to steal moments of privacy in the crowded city. It’s an energy that is embodied in how these scenes were shot.

As Kapadia explained on the podcast, film production is expensive in Mumbai, and to skirt the need for permits and infrastructure required to “properly” shoot the night scenes, she and Das would go out with their small DSLR camera (that looks like a still photography camera) to find the compositions at exterior locations that would be friendly to the bare bones crew, and return with their cast at night.

Temporal Storytelling

The energy of the city is also captured in how Kapadia and editor Clément Pinteaux cut the film, which was part of how the director wanted to structure the film’s presentation of time.

“I had this idea that I wanted to play with temporality, which is something that in cinema is such a joy to do,” said Kapadia. “And I felt that time, the sense of time could add to those layers in the script, and so the first half is really quick, but also because in cities and the lives that these women lead, there’s no time to dream about yourself and think, ‘Oh, woe is me.’”

This first section of the film takes place over many days, but when the film shifts to the coastal Ratnagiri region — as Prabha and Anu make the trip to help their colleague Parvaty (Chhaya Kadam) move back home after losing her apartment — there is a significant shift.

“I wanted the second part to be just one very long day, and to feel time really slowed down, almost as if we reach a sort of timelessness, which you feel in dreams,” said Kapadia.

The Color, Light, and Sound of Dreams

‘All We Imagine as Light’Janus FIlms/Courtesy Everett Collection

‘All We Imagine as Light’Janus FIlms/Courtesy Everett CollectionThis shift is not only formally marked with longer shots and less edits, Kapadia reached for a distinct visual and aural presentation as well. Kapadia paused production after shooting the first half of the film in Mumbai — in part because she wanted to embrace the approach taken on her documentaries, where taking time to edit can better inform what and how she shot the rest of the movie — but also to wait out monsoon season, and give the more dream-like second half a different light and color palette.

“The colors of the monsoon are more blue and gray, and the colors of Ratnagiri [after the monsoons] are more red and yellow — red because the soil is red, kind of terracotta color,” said Kapadia. “We wanted the sun to be felt, because in the first half you don’t feel any direct sunlight at all, but in the second half to have so much sun that sometimes images are even bleached out and you completely lose details. We felt that we could play with this feeling of a dreamlike state with the sunlight.”

Kapadia also reached for a more dreamlike soundscape in the Ratnagiri section. She drew inspiration from how Federico Fellini used sound. This is best on display in the film’s dramatic climax in which a man is saved from drowning. While being an extremely dramatic scene, it lasts for almost ten minutes, and there’s a sense time is being extended — the exact opposite of what you’d expect from the action-packed moment.

“I really like to work in this way of sound where you feel that something is objectively real and you’re hearing very real sounds, and then those very sounds become as if they’re coming from inside somewhere. I felt that going from this external world into Prabha’s internal mind space, sound could play an interesting role,” said Kapadia of the drowning scene. “I was very interested in how Fellini does this, especially in ‘8 1/2,’ where suddenly it goes into these dream sequences with just a gentle track, and the sound of the wind and the light changing. I am mesmerized by how it’s almost theatrical, but with more emphasis on sound.”

To hear Kapadia’s full Toolkit interview, subscribe to the Toolkit podcast on Apple, Spotify, or your favorite podcast platform. You can also watch the full interview below, or subscribe to IndieWire’s YouTube page.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·