Voiceover narration is designed to provide information not readily available onscreen. Whether it’s a third-person narrator keying us into the inner musings of the characters we’re watching or a protagonist offering us their own presumably unfiltered thoughts, this storytelling tool lives to tell, not to show. That’s perhaps why it’s often dismissed as a narrative crutch, especially within an audiovisual medium like television in which image is king. To spell out an emotion in words feels redundant at best and unnecessary at worst. Deployed well, though, it can be a thrilling way of making us question what it is we’re watching and how it is that stories are shaped by how they’re told and to what end—and, most crucially, by whom.

Apple TV+’s Disclaimer, which marks Academy Award winner Alfonso Cuarón’s entry into television, understands all too well how voiceover narration can further complicate and illustrate a story about trust and guilt, about personal biases and individual experiences, about what we remember and how that informs the stories we tell others, but especially the stories we tell to and about ourselves. The miniseries, adapted from Renée Knight’s novel of the same name, utilizes not one but two narrators. It’s but one way in which this tale, of a documentary filmmaker who finds her life upended when a novel quite clearly modeled on an instance from her past she’s long hoped to forget arrives at her doorstep, is intent on complicating the very nature of storytelling. And in so doing it crafts one of the most inventive uses of voiceover in contemporary American television.

The moment we first meet Catherine Ravenscroft (Cate Blanchett) is the moment Disclaimer presents its central thesis: “Beware of narrative and form,” Christiane Amanpour tells an audience gathered to bestow on Catherine an award for her storied career in documentary filmmaking. “Their power can bring us closer to the truth but they can also be a weapon with a great power to manipulate.” Over its first four episodes, Disclaimer has made this all too obvious. Shuttling between three different timelines (and attendant points of view), this careful character study in triplicate constantly warns us to not take what we see for granted. It asks us, as Catherine’s work had done for the likes of Amanpour, to question what it is we’re watching and why, perhaps, we’re being allowed to see and hear what’s in front of us.

There is a disorienting effect to the way Cuarón, who wrote and directed all episodes of this London-set miniseries, has translated Knight’s prose on the screen. In the novel, chapters alternate between a third-person narrator detailing Catherine’s unraveling and a first-person one walking us through how and why they decided to target Catherine by publishing a book that features the line that gives the novel its title: “Any resemblance to persons living or dead is not a coincidence.” It’s that disclaimer which eventually rattles Catherine once she realizes a holiday trip to Italy where a fateful meeting with a young man ended in tragedy has now been turned into a novel titled The Perfect Stranger. That moment is what Knight opens her novel with: It’s late at night, and Catherine is throwing up in the bathroom. She wards off her doting husband and steadies herself in the mirror, unsure how or why this novel with that pointed disclaimer has found her way to her home. It feels like an accusation. A threat even. On the page, the scene remains rather chilling. “She studies herself in this new harsh light,” Knight writes, “and wets a flannel, wiping her mouth then pressing it against her eyes as if she can extinguish the fear in them.”

When Cuarón stages this very same scene, with the languid long takes he and cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki have made their signature stylistic flourish, the moment is made all the more discomforting by the voiceover that accompanies it. For on the small screen, the Mexican filmmaker has turned Knight’s prose into a second-person narrator. British actor Indira Varma doesn’t (merely) describe what Catherine is doing and thinking; she does so by addressing us. “You have seen this face before,” she says as Blanchett’s Catherine wipes her face.” You had hoped never to see it again. Your mask has fallen.” Second-person narration has a way of bringing us both closer and further away from the characters at hand: By being placed in Catherine’s shoes, we’re encouraged to feel not just for her but alongside her. Yet by knowing how far away we are from her, it’s a futile endeavor. We have not seen that face before. We do not know what mask Disclaimer’s narrator is talking about. For much of these first few episodes, it’s hard to understand what truly is going through Catherine’s mind as she tries to figure out who is unearthing that Italy trip and the tragedy that ensued and to what end. But she remains a cipher, and the voiceover narration, which would usually help elucidate her feelings for us an avid audience, here instead finds ways of keeping her at a discomfiting distance. This is made all the more obvious by the very tone Varma takes; hers is a dispassionate narrator, one whose cool tenor makes it clear she’s not taking any sides, just observing dispassionately what occurs to Catherine and her surroundings.

On the other end of the spectrum is Kevin Kline, the series’ other narrator. Where Varma is almost aloof, Kline’s Stephen Brigstocke is a frantic and overly sentimental man. His voiceover takes us inside his mind, which is often racing with ideas and grievances (not to mention grief). As we’ve learned, Stephen and his wife Nancy (Lesley Manville) lost their son Jonathan (played in sun-dappled flashbacks by Louis Partridge) years ago while he was backpacking through Europe. It is he who has published a novel retracing Jonathan’s final days in Italy—and he who’s made it a point to, it seems, avenge not just his son but his wife, who died of cancer and left him with an empty house that had been devoid of feeling long before. As Stephen tells us in voiceover in episode “IV,” “When Jonathan died, Nancy shattered. Her mind shrank into a small, dark thing, and all she could think about was our son’s absence.” There’s bitterness in his voice. And melancholy, too. He sounds like a broken man trying to make sense of what first broke his family. As if to stress the darkness Stephen is describing, Cuarón offers up an image of a crow atop the Brigstocke’s outdoor grill (presumably unused since Stephen and Nancy first heard of Jonathan’s death abroad), unperturbed by the feelings Brigstocke is voicing for our benefit.

If Varma’s second-person narration keeps us in an oddly intimate yet distanced relationship with Catherine, Kline’s own voiceover makes us feel for him and Nancy even (or especially) when his actions get crueler and crueler. Leaving the crow behind and following Stephen up the stairs as he calls out to Nancy after disposing of a dead fish from their fish tank, the former schoolteacher finds his wife submerged in their tub. She’s not tried to kill herself (or so she claims). She was hoping to see what Jonathan had felt before he’d drowned. It’s a harrowing scene, one that further helps align our sympathies with the Brigstockes, who seem to live worlds away from the bourgeois affluence of Catherine, her husband Robert (Sacha Baron Cohen), and their son Nicholas (Kodi Smit-McPhee).

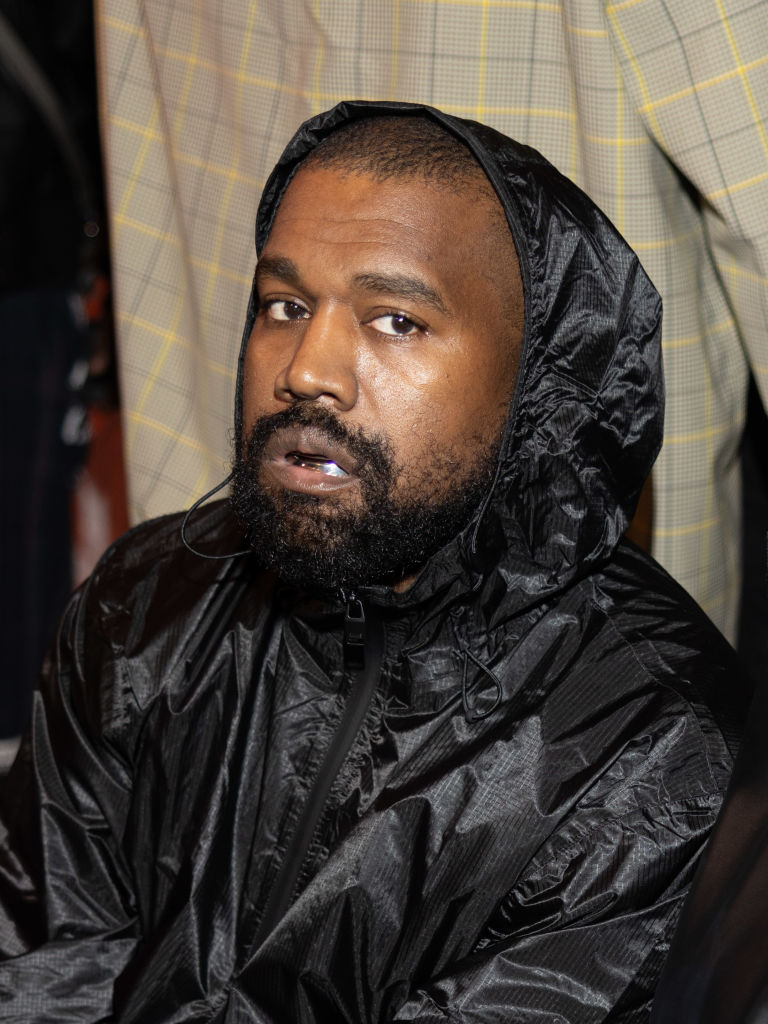

Photo: Apple TV+

It’s that placid homeliness which The Perfect Stranger aims to fracture. Only, while Knight’s novel offered its readers short excerpts from it, Cuarón opts to offer his viewers no words from it at all. Instead, he plunges us to a honeyed, sunny Italy that’s been dreamed up by Nancy’s manuscript-turned-novel but that’s being presented as what really happened when a young, harried Catherine (who was holidaying with Nicholas, then just a child) met Jonathan (who was traveling solo, then just a dashing young man). As presented in “IV,” those scenes led to a climactic moment of sexual abandon between the two, captured in snapshots by Jonathan’s camera, which Nancy used to color in those final days in her fictionalized account and which Stephen has used to bait Robert Ravenscroft into reading said published account.

“Robert has to stop reading,” we hear Varma say in this most recent episode as those steamy scenes play out in his head (and on our screens, in turn). “He can only trust this printed word, and there is enough of his wife in the book for him to recognize her.” He’s being ginned up by words about his wife that paint a picture of her that Catherine herself cannot quite bring herself to recognize (the mask having fallen, as we’d been told in episode “I”). “The shock you felt when Robert confronted you with the photographs slices through you again,” we’re later informed. “He wants you to be punished. He thinks you deserve it.” Such a line speaks to why Cuarón’s use of voiceover narration feels so thrilling. He’s placed his audience in a truly uncomfortable position, not just by having to wade into the embittered first person of Stephen’s righteous grief but also by being constantly made to feel ill at ease at being addressed with such cutting words. That “you” is meant to rattle us even as it cannot really let us wholly empathize with Catherine. Much like how she feels, her story has gotten away from her, and it’s all these other characters who are now narrating it for and to her.

As a filmmaker, Cuarón has long been formally invested in what his camera can show us. His predilection for roving, long shots that usher you in and out of spaces, controlling with self-conscious flair what it is you can see (or not) in any given scene, shines through again here in Disclaimer. But it is his decision to fracture his audience’s attention and empathy through his competing yet complementary voiceover narrations—arguably the most inspiring use of them on American TV in quite a while—that turns this literary adaptation into a thrilling piece of television. One that refuses the simplicity of either showing or telling, finding instead a way to make us wary of both. And perhaps, in what feels like the tacit disclaimer it espouses at the start of each episodes, of all storytelling in turn.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·