A map of drought conditions across the U.S. has revealed that nearly three-quarters of the country is currently experiencing some form of drought.

As of October 29, 78 percent of the American population was living in an area affected by some degree of drought condition, according to data from the U.S. Drought Monitor.

This is the highest proportion affected by drought since the U.S. Drought Monitor's records began 25 years ago.

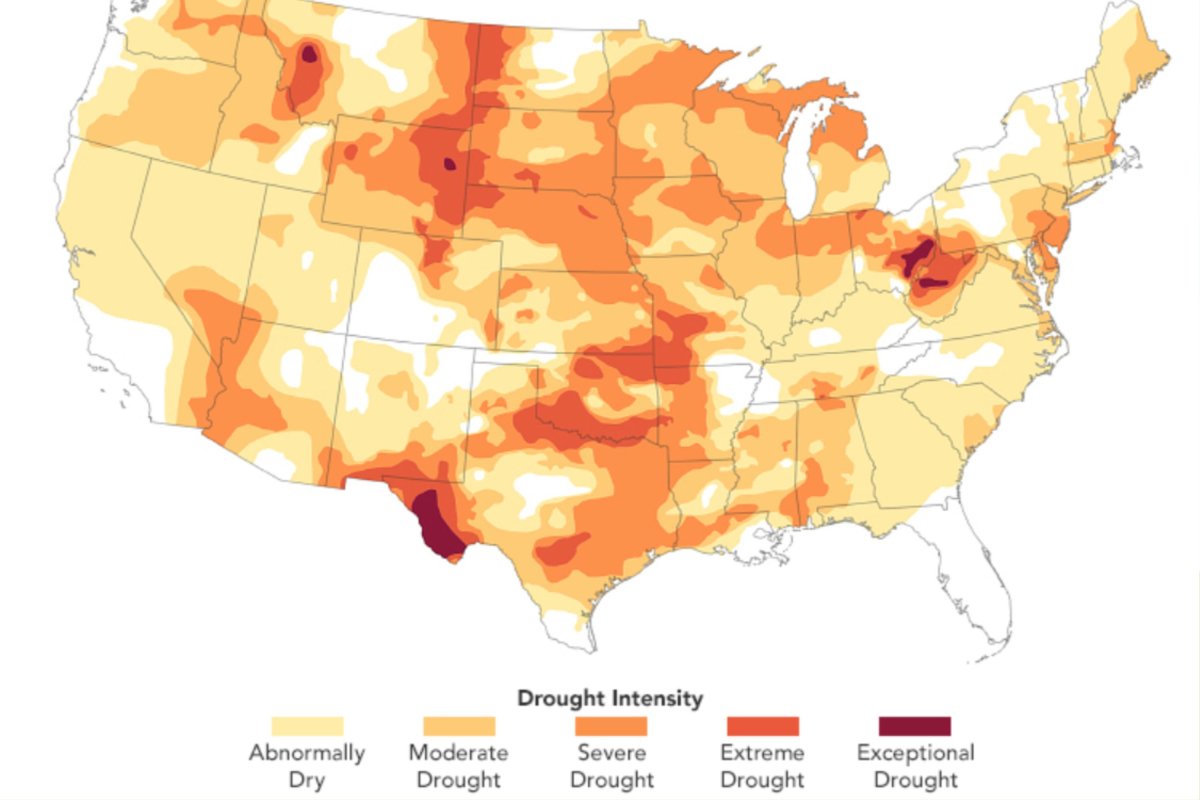

By area, the Drought Monitor reveals that 73.18 percent of land across the U.S. and Puerto Rico was under some kind of drought. These conditions include five categories: Abnormally Dry, Moderate Drought, Severe Drought, Extreme Drought, and Exceptional Drought.

Only 26.82 percent of land was completely drought-free, 27.91 percent Abnormally Dry, 22.21 percent under Moderate Drought, 17.61 percent under Severe Drought, 4.92 percent under Extreme Drought, and 0.53 percent under Exceptional Drought.

The week before, on October 21, 33.35 percent of the country was drought-free, and as of the end of July, 58.44 percent of the country was out of drought.

The Drought Monitor map reveals that worst-hit areas include southwestern and northern Texas, Ohio, West Virginia, Oklahoma, Missouri, Wyoming, and Montana.

This drought comes as much of the country saw much warmer temperatures and drier weather than normal during October, with over 100 weather stations seeing no rain for the entire month, according to the Southeast Regional Climate Center. The driest October on record was seen for 70 of these weather stations.

The rapid increase in dry conditions and fall in precipitation across the U.S. in recent months is due to something called a "flash drought" in many areas.

"This fall [in precipitation] has been a prime example of flash drought across parts of the U.S.," Jason Otkin, a meteorologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, wrote in a NASA Earth Observatory post. "These events can take people by surprise because you can quickly go from being drought-free to having severe drought conditions."

Flash droughts are rapid-onset droughts that develop much more quickly than traditional droughts, often within a few weeks to a couple of months. Unlike typical droughts, which can develop over extended periods, flash droughts emerge due to a combination of high temperatures, low humidity, intense sunlight, and strong winds, which speed up the drying of soils and vegetation.

"When this occurs, industries that depend on surface water can be greatly impacted, especially agriculture. Flash drought is also challenging to forecast/predict but can lead to significant ecological and socioeconomic impacts as it tends to catch planners off guard," Jeffrey Basara, chair of the Department of Environmental, Earth, and Atmospheric Sciences at the University of Massachusetts Lowell, previously told Newsweek.

According to a paper published by Otkin and others last year in the journal Science, "droughts have begun to intensify more rapidly since the 1950s" as a result of climate change. This has resulted in flash droughts becoming more frequent worldwide.

"This trend, which makes drought monitoring and forecasting more difficult, is associated with greater evapotranspiration and precipitation deficits caused by anthropogenic climate change and is projected to expand to all land areas in the future," the researchers wrote.

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about drought? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

References

Yuan, X., Wang, Y., Ji, P., Wu, P., Sheffield, J., & Otkin, J. A. (2023). A global transition to flash droughts under climate change. Science, 380(6641), 187–191. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn6301

English (US) ·

English (US) ·