A father with a fiery temper sat on the edge of his seat, watching the Calabasas High School tennis match intently. His head turned left and right, back and forth, as if an invisible thread connected him to one player: Erik Menendez.

"He was one of those parents you knew would lose his temper and get angry if his child wasn't doing well, blaming others for any failures," Alison Triessl (whose maiden name was Bloom), a member of the girls' tennis team, told Newsweek.

Triessl called José Menendez "one of the strictest, meanest, most demeaning" fathers she had ever seen.

"He was cruel to Erik and he put him down all the time and he had a fiery temper," Triessl said. "There was no doubt that when he was around, you could tell that Erik was intimidated by him, there was no question."

Erik Menendez ranked 44th in the United States at one point, showcasing his talent as a tennis prodigy.

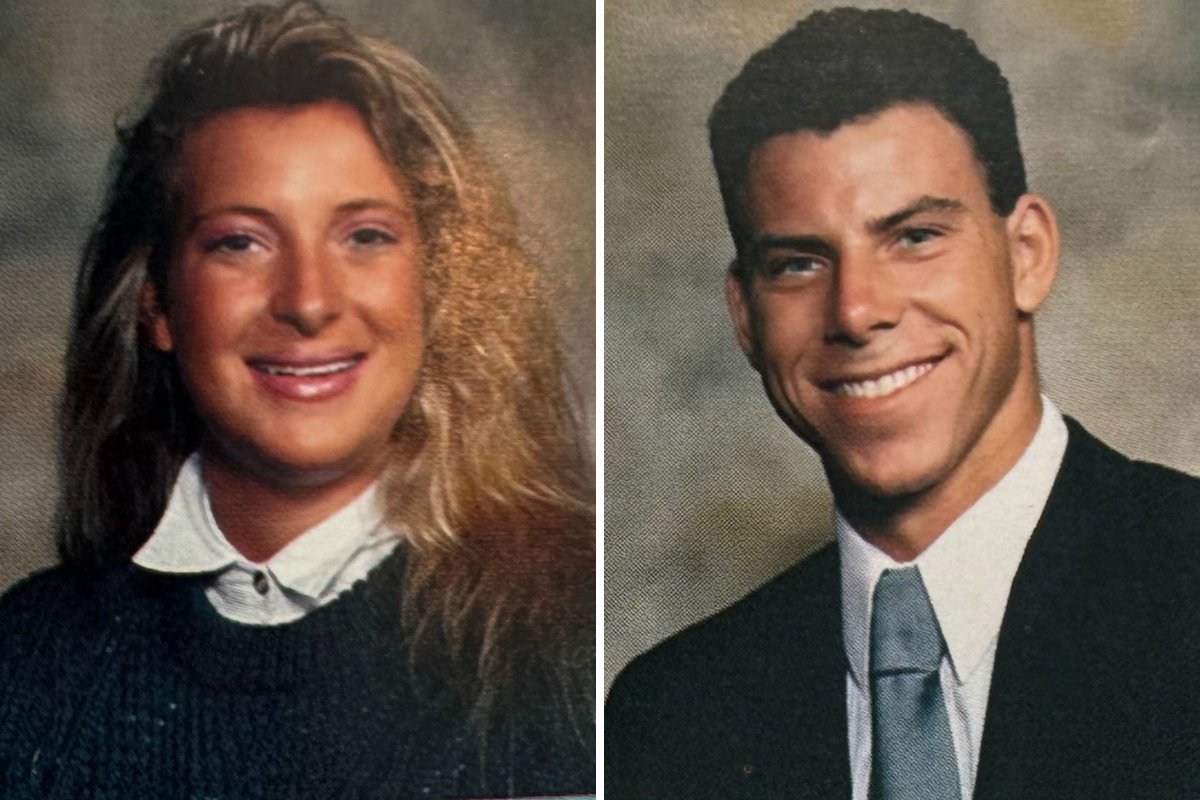

Off the court, Triessl and Erik Menendez were classmates, study partners, and friends in high school.

"Erik was extremely bright, but he was also very arrogant and cocky and a bit conceited and spoiled," Triessl said. "But he was extremely, extremely bright. I would study with him, so we were more than just acquaintances. I would classify us as friends."

While Erik Menendez came across as bright and arrogant at school, a darker reality awaited behind the closed doors of his Beverly Hills home.

"The level of pressure that José would put Erik into in a public setting, I could only imagine what it was like when they were at home behind closed doors," Triessl said. "And I imagined it to be horrific."

On August 20, 1989, Erik and his brother Lyle Menendez gunned down their parents, José and Kitty Menendez with 14 shots as the couple sat watching TV in the den of their home.

The duo shot José five times, including once at point-blank range with a shotgun aimed at the back of his head. As Kitty attempted to crawl away, Lyle shot her in the face with a shotgun. In total, she was shot nine times.

Lyle, who was then 21, and Erik, then 18, admitted they shot-gunned their entertainment executive father and their mother, but said they feared their parents were about to kill them to prevent the disclosure of the father's long-term sexual molestation of Erik.

'Lack of sadness and concern'

Triessl remembers meeting Erik Menendez and friends at a Calabasas yogurt shop after the murders. Unaware Erik Menendez and his brother had killed their parents, they gathered to console him during the difficult time.

"I was struck by the lack of sadness and concern," Triessl said. "He talked about money and cars and watches and going to Israel. I remember that distinctly."

Triessl continued, "I came home and spoke to my father, who is a psychiatrist, and I said to him, 'It is so strange to me Erik really didn't seem that sad.' And he said, 'Well, people experience grief in different ways.' And I said, 'Yes, but this was strange.'"

'So brutal and so vicious'

In March 1990, several months later, authorities arrested Erik and Lyle Menendez for the murders of their parents. The brothers would soon face trial.

"We were all surprised. We were all surprised because this was so brutal and so vicious," Triessl said. "His mother's face had been shot off. The idea that someone that we knew would do that to their own parents was really shocking to the conscience."

In the first Menendez brothers' trial, which began in 1993, Lyle and Erik were charged with the 1989 murders of their parents.

Well-known defense attorney Leslie Abramson represented Erik. She gained attention for her compelling defense strategy, which argued the brothers had killed their parents in self-defense after enduring years of abuse at the hands of José.

"His lawyer, Leslie Abramson, had a good reputation, but it was one of being fierce, like a lioness, and controversial," Triessl, now a criminal defense attorney, said. "I remember when I heard, while I was in college, that the defense was going to be that they had been sexually assaulted. I was surprised by it."

"I did not have the impression that he had been sexually assaulted or molested by his parents."

'Something was horribly wrong in that family'

Triessl continued, "I was never in that bedroom. I can't tell you whether or not they were molested, but I do remember saying something was horribly wrong in that family. Kitty Menendez was always very quiet. She didn't say very much."

However, she pointed out it was a different time, and back then, the issue of sexual abuse, particularly involving boys, wasn't openly discussed or seen as a likely explanation.

Deborah Tuerkheimer, a former Manhattan prosecutor and author of Credible, told Newsweek boys who are victims of sexual abuse and assault face additional challenges because such cases are less common and often less acknowledged, with these difficulties being even greater decades ago.

"When victims don't behave or look like we expect them to behave or look, we tend to find them not credible and boys don't really fit into the popular understanding of who's a victim of abuse," the author said.

Jennifer Simmons Kaleba, Vice President of Communications of RAINN told Newsweek not being believed from the beginning can be one of the most damaging experiences for a survivor. The level of belief they receive shapes their entire journey, impacting their chances of achieving legal justice.

The trial ended with two deadlocked juries, unable to agree on whether the brothers were guilty of murder or acted out of fear. This led to a mistrial on January 28, 1994, and set the stage for a second trial in 1995.

"It did make us think, well, is it just because the father was so mean to them? Was it just over the money? Because there were questions over the inheritance and a lot of money was at stake. Or was there something more? It left a lot of questions in our minds," Triessl said.

Prosecutors argued there was no evidence of the alleged molestation and the judge excluded most abuse evidence from the second trial. They said the sons were motivated by a desire to inherit their parents' multimillion-dollar estate.

In 1996, the jury convicted both brothers of first-degree murder, and they received life sentences without the possibility of parole. The verdict highlighted the complexity of the case and the differing views on justice and mental health issues in the context of violent crime.

Lyle, 56, and Erik, 53, have spent three decades behind bars. Now, it's the Menendez brothers' turn for a potential chance at freedom.

"Since that time, I've gone to college, I've gone to law school, I've gotten married, I've raised children," Triessl said. "And Erik has basically remained in a prison cell all of those years."

On October 24, Gascón announced plans to recommend the Menendez brothers' life sentences without the possibility of parole be replaced with a 50-years-to-life sentence for murder. He said, due to their ages at the time of the crimes, they would be eligible for parole immediately.

Triessl, who recently watched The Menendez Murders documentary on Netflix, tuned in to hear what the brothers would say after 30 years.

"I have been very impressed with the amount of reform and rehabilitation that they have done, simply because they were sentenced to life without the possibility of parole," Triessl said.

She continued, "There really was no incentive for them to start all these programs or have these support groups, because a lot of people in prison will do a lot of things to be on their best behavior so that when their parole hearing comes up, they can say, 'Hey, I did X, Y, and Z.' Here, they were never going to have a parole hearing. So it seems that they did make real change and real reform on their own."

The court has set a date for Erik and Lyle Menendez on December 11 at the Van Nuys Courthouse, where the brothers previously faced trial in 1993 and 1995.

Do you have a story Newsweek should be covering? Do you have any questions about this story or the Menendez Brothers? Contact LiveNews@newsweek.com

English (US) ·

English (US) ·