The Grand Canyon may rewrite the textbooks on the Cambrian Explosion—a key turning point in Earth's history when there was a sudden boom in complex life and the emergence of all the major animal groups seen alive today.

This is the conclusion of a U.S. team of researchers, led by the University of New Mexico and the Utah State University, who studied the "Tonto Group", a 0.3-mile-thick collection of five rock formations that are exposed along the sides of the canyon.

"The Tonto Group of Grand Canyon holds a treasure trove of sedimentary layers and fossils chronicling the Cambrian Explosion some 500 million years ago," paper author and Utah State University geology professor Carol Dehler said in a statement.

At the time the Tonto Group was being laid down, sea levels were rising, covering the submerged land with emerging marine life. However, the team has determined that the traditional model of this process—developed from a previous study of the Tonto Group in the 1940s—oversimplified this process.

The Tonto Group, Dehler said, is teaching us "about sea-level rise and the effects of catastrophic tropical storms—probably more powerful than today's devastating hurricanes.

"This occurred in a world without land plants and during a period of very hot temperatures when the Earth was ice-free.

"Sea levels were so high that sediments like the Tonto Group were deposited atop most continents in environments that allowed rapid expansion of animal diversity of Earth."

The very same rocks in the Grand Canyon were used nearly 80 years ago by the geologist Eddy McKee to form the classic geological model for the advance of seas across continents—a phenomenon dubbed "marine transgression."

Under the McKee model, marine transgression involves a gradual deepening and corresponding changes in sedimentary environments.

According to the team, however, instead of one major transgression with only minor regressions (where the water recedes), there are in fact five sedimentary sequences, the lower three of which are separated by gaps in the rock record where material was eroded away.

And rather than being fully marine, these sequences were formed in a varied mix of environments, with braided coastal plains, wind-blown sediments and different shallow marine settings—the result of a mixture of sea level changes and different rates of local subsidence.

The University of New Mexico's Professor Karl Karlstrom, a co-author of the paper, explained: "Our new model for deposition of the Tonto Group is much more nuanced, showing a mixture of marine and non-marine settings, breaks (or "unconformities") when no sediment was being deposited, and a much faster tempo of evolution," he said in a statement.

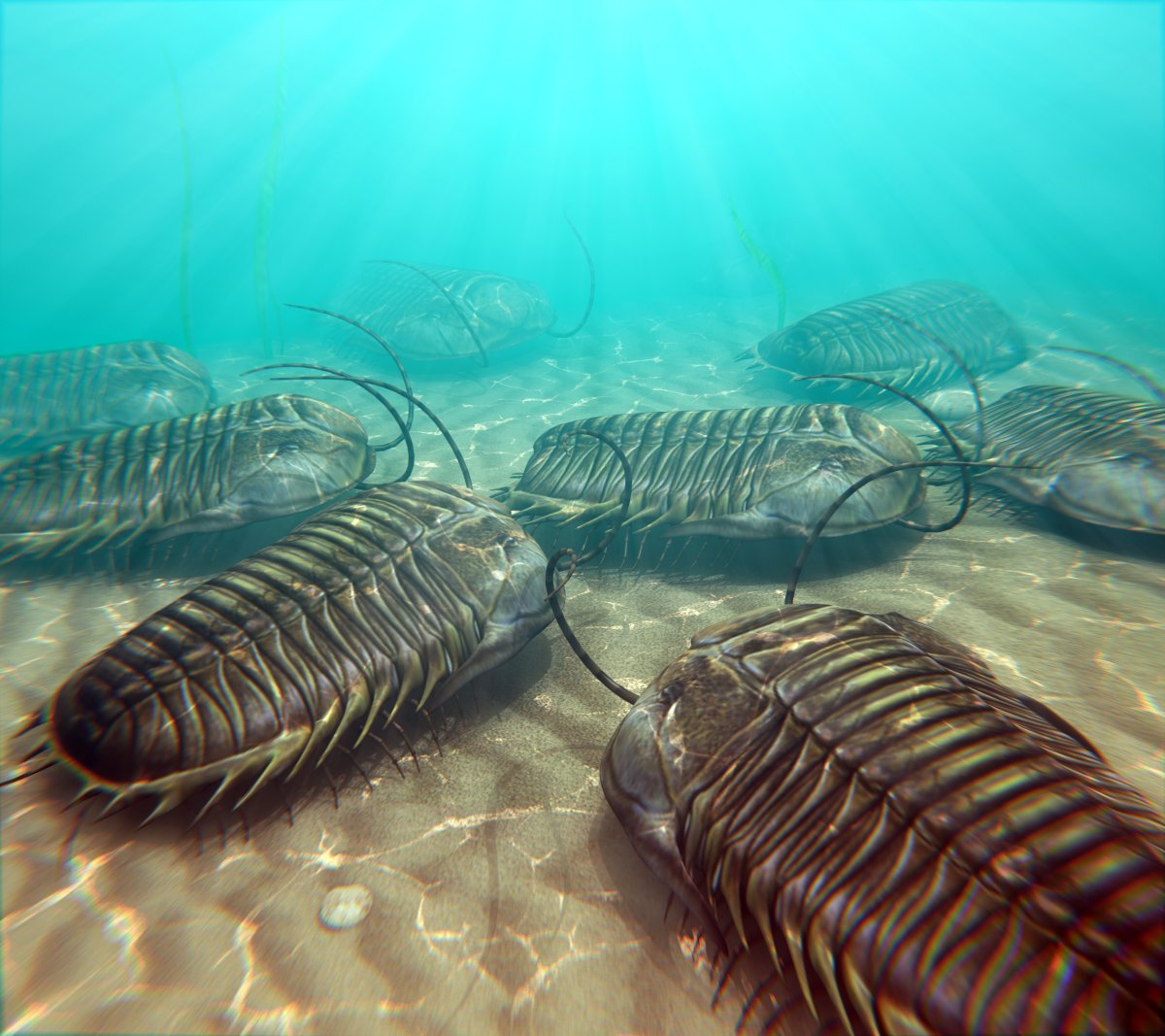

For example, the dating of the rocks with the aid of zircon crystals—which are like natural little time capsules—has revealed that species of aquatic, pill bug-like arthropods known as trilobites radiated and then went extinct at a rapid, sub-million-year tempo.

"Even more than before, the Tonto Group of Grand Canyon remains one of the most important Cambrian type sections in the world, because of its complete exposure."

The team's discoveries, Denver Museum of Nature and Science geologist James Hagadorn added, are a reminder that science is a process.

He concluded: "Our work in the Grand Canyon—one of the world's most well-known and beloved landscapes—connects people to this science in a very personal way."

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about the Cambrian Explosion? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Reference

Dehler, C., Sundberg, F., Karlstrom, K., Crossey, L., Schmitz, M., Rowland, S., & Hagadorn, J. (2024). The Cambrian of the Grand Canyon: Refinement of a classic stratigraphic model. GSA Today, 34(11), https://doi.org/10.1130/GSATG604A.1

English (US) ·

English (US) ·