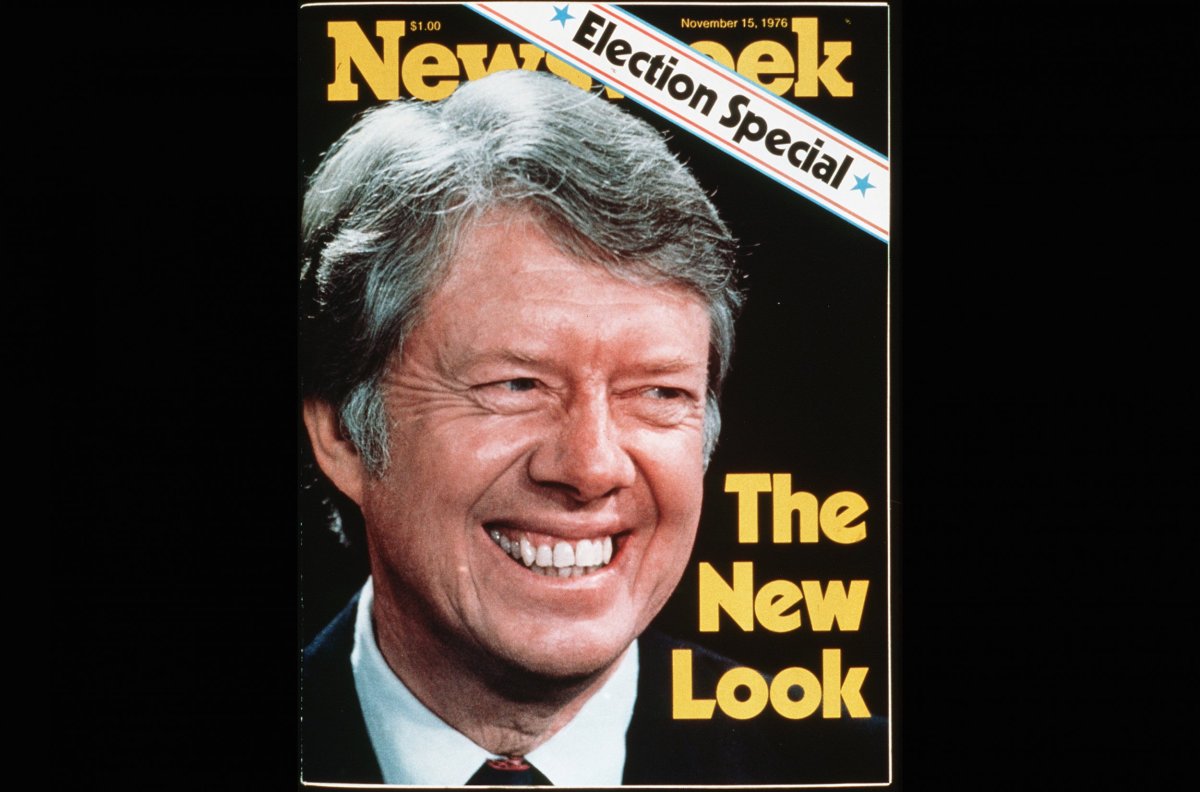

This article was originally published on November 15, 1976. The former president died on December 29, 2024.

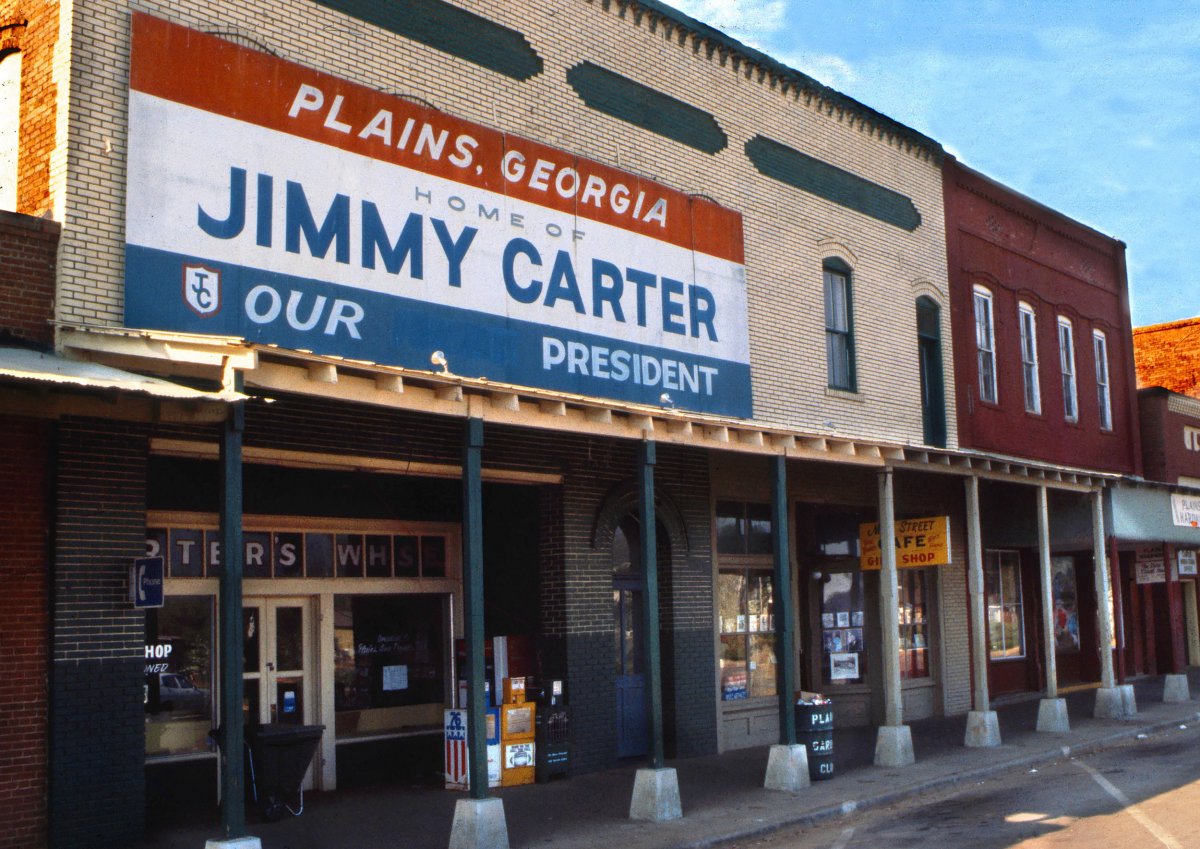

For Jimmy Carter, the long-distance run was over—an astonishing two-year, half-million-mile journey from a Georgia boondock named Plains to the most powerful job in the world. He had spent the last anxious weeks of that marathon watching the last of his 33-point summer lead melt away to what the major polls sized up as a dead heat with Gerald Ford. But at the very end, America's Democratic majority came home to Carter in a late surge that flooded polling places in party strongholds across the nation and stopped Ford's gallant comeback just short of victory. As the returns chattered in through a long razor-edge election night, both men made their marks in history: Ford as the first Chief Executive since Herbert Hoover to be voted out of office—and Carter as the first Deep Southerner since before the Civil War to be elected President of the United States.

Carter's edge, just as the polls predicted, was far too close for comfort: it took till the morning after to nail down his 51-48 majority of the popular vote and his 297-235 lead in the electoral college, with Oregon's six votes hanging on a tally of absentee ballots. His triumph was nonetheless impressive: he resolidified the Democratic South for the first time since the New Deal days, split the industrial North with the President, helped his party hold its swollen majorities in Congress and the statehouses, and in the end recovered the White House from the Republicans for the first time since Lyndon Johnson. But Ford ran him a surprisingly close race, and Eugene McCarthy's third-party insurgency aggravated the suspense by tipping several states out of the Carter column. The Georgian was a bare two electoral votes over the top (with 272) when he descended from his Atlanta hotel suite to claim the Presidency and tell his cheering campaign workers: "I pray I can live up to your confidence and never disappoint you."

Ford was not so quick to concede the end of his 27-month accidental Presidency, sleeping on the returns overnight and closeting himself next morning with aides to consider the possibilities of challenging the outcome. The verdict was a unanimous no, and by midday, the President—puffy-eyed, teary and laryngitic—met the press surrounded by his family to make his concession and his farewells. To spare his throat, Betty read his telegram of surrender, addressed "Dear Jimmy," signed "Jerry Ford" and accepting with consummate style that Carter had "won our long and intense struggle for the Presidency. He tendered his congratulations, his prayers and his support. His daughter, Susan, wept. His son Steve struggled for control. Ford himself moved shiny-eyed into the press of newsmen, extending handshakes and thanks. "We lost," he said, "in the last quarter."

Carter's own mandate to govern was shadowed, and not just by the skimpiness of his winning edge. The Congress is preternaturally wary of him, given his combative relations with the Georgia legislature during his gubernatorial years; Carter felt obliged in the midst of his long election-night vigil to put in a peace-keeping call to House Speaker-to-be Thomas P. (Tip) O'Neill and enthuse: "I'm going to be President, you're going to be Speaker, and we're going to get along fine." Carter is likewise an incompletely acquired taste for the party and trade-union organization men who helped elect him, and their joylessness in his election was manifest. "I think," said one ranking party leader, "we have a winner—for better or for worse."

Carter is further burdened by a kind of lingering public unease over who he really is and what he really stands for. Election Day polling by NBC News suggested that mistrust of Carter did not count decisively against him—that he in fact rated about as well as Ford on questions of honesty and credibility. But nearly half the electorate found him less than completely trustworthy, a considerable residue of suspicion barely three months before his coming to power. Some of the Mr. Outside glow of his candidacy rubbed off in his final days of dependency on the Mssrs. Inside of the Democratic Establishment. The midwives of his victory in the end were old-style delivery pros like the AFL-CIO's George Meany and national party chairman Robert Strauss; Carter in the end required rescue by the men he had once run against.

That he needed help was in part a tribute to Gerald Ford's autumn recovery—a come-from-behind scramble matching Harry Truman's in 1948 in everything except its happy ending. The strategy came from from a 199-page staff paper known in the White House as The Book and considered so sensitive that only three copies were run off besides Ford's own. It opened with some uncommonly blunt lese majesty: the assertions that most Americans did not consider Ford "a strong, decisive leader" and that his shortcomings as a campaigner only made matters worse. Out of these premises grew the celebrated Rose Garden strategy—keeping Ford home acting Presidential till the last ten days and making an issue instead of what The Book described as Carter's accident-prone campaign; Ford achieved what the Gallup organization described as the greatest comeback in polling history.

'We Won This Election For Him'

What stopped him at the last, in the common judgment of the professionals, was less Jimmy Carter than a simple arithmetical fact—that there are roughly twice as many Democrats as Republicans in America. Carter's main contribution to the demography of his victory was the South, as nearly solid for him as it has been for any Democrat since Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1944; he lost Virginia narrowly, but carried everything else from the Carolinas to the Rio Grande. What Carter did less sure-handedly, and in the end only with help, was sell his evangelical politics in the urban North and West. He won finally as Democrats historically have won—mobilizing traditional Democratic voters by traditional Democratic means on traditional Democratic issues. The cost was the debt he incurred. "We won this election for him," said one big-city party leader. "The question is whether he'll show us any gratitude."

The face of his victory was indeed distinctly familiar. He did smashingly with black voters, solidly with union members and hyphenated Americans, decently with Catholics and Jews—all mainstays of the old Democratic coalition. He fared just well enough in the industrial North, though McCarthy's damaging incursions turned Carter's election night into an agony of waiting and may have cost him more than 40 electoral votes. He profited enormously by the large, late-blooming turnout, some of it flogged to the polls by a massive Democratic get-out-the-vote drive, some moved by the much-advertised fact that the race was close and every ballot meaningful. NBC's polling data suggested that one voter in five chose sides only in the final week of the campaign—and that a heavy majority of them, moved more by pocketbook issues than Carter's personal attractions, voted the Democratic line.

The results left the Republicans reduced, bitter and more desperate than ever for a new hero. The day's returns did thrust forward some fresh faces to help console the party till next time—among them James Thompson, the racket-busting governor-elect of Illinois, and a handsome young freshman Senate class including Richard Lugar of Indiana, John C. Danforth of Missouri and H. John Heinz III of Pennsylvania. The year's labors profited Texas's ex-Democratic ex-Gov. John Connally as well, backing up his known ambitions with a pocketful of campaign chits from Republican Congressional candidates around the country. But the real message of 1976 was how narrow the party's base has become, and how little its nomination may be worth if it could not return a sitting President to office. "This party is a disaster," said a national committee leader. "Maybe you just start all over again."

Carter, by contrast, wore a winner's ineluctable smile as he thanked his followers—"I love every one of you"—and then flew home next morning to begin preparing for his assumption of Presidential power less than three months hence. The first entry in his calendar for the interregnum was a week's R&R in Plains, working the telephone, pondering his briefing books and mending in flesh and spirit after 22 months on the road. But the transition team he put quietly to work last spring just in case will set up shop in Washington by midmonth, and Carter is expected to follow at least part-time rather than require job applicants and issues people to make the trek to Plains. His people have already supplied him with the names and pedigrees of perhaps 75 Cabinet prospects; their expectation is that Carter will start early by naming a Secretary of State, to indicate his own interest in foreign affairs—and, said one aide, "to signal the world there's been a changing of the guard."

Down to the Last Bitter Days

Plains in the meantime will become the seat of a two-month shadow government while Ford plays out the final days of what has suddenly become a lame-duck Administration. There was a tinge of bitterness in his overnight delay in wiring or phoning his concession to the winning candidate. "There are few people the President dislikes as much as he does Jimmy Carter," one senior hand confessed. Still, once Ford gets back from a week's recuperation in Palm Springs, he will sit down to a deskful of pressing business that cannot all be bucked to the new crowd—the shaky progress toward a Rhodesian settlement, the languishing SALT talks with the Soviets, the potential damage to the U.S. economy of an impending rise in imported oil prices, the final scrutiny of the last Ford budget. It is said in the White House that he might like to treat himself as well to one last Presidential spectacular—perhaps a trip to the Middle East.

And then it will be Jimmy Carter's turn. He made his emotional homecoming to Plains in the daybreak after his longest night, discovering a crowd of townspeople who had been waiting up the whole while in Main Street. "I told you I didn't intend to lose," he said; then, suddenly, his eyes flooded up, and he turned away into Rosalynn's wet-eyed embrace. His discipline quickly reasserted itself, and with it his store of homilies. "I see," he said, into the spreading morning, "the sun is rising on a beautiful new day." But he enters upon it with a slender mandate, untried skills at statecraft, and eleven weeks to prepare himself for his day in the sun.

—Peter Goldman with Hal Bruno and James Doyle

English (US) ·

English (US) ·