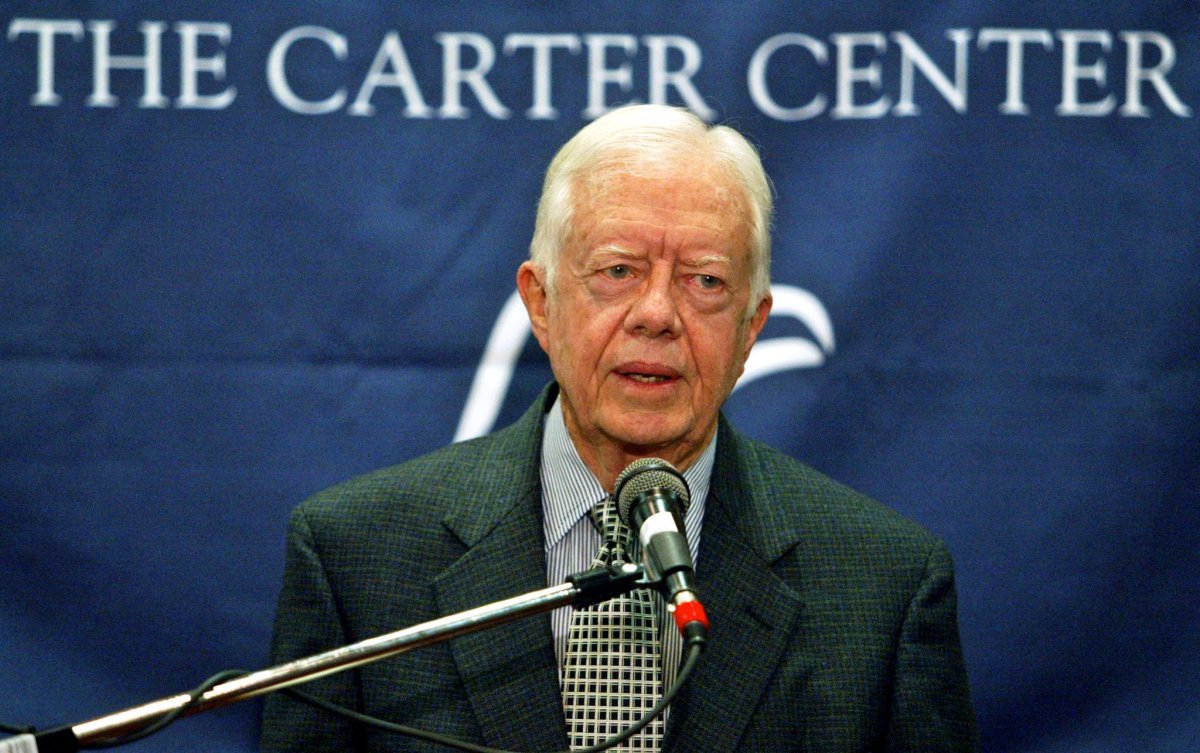

Like most presidencies, Jimmy Carter's will face history's judgment in determining whether its fiascos—rampant inflation, gas shortages, the failed U.S. military efforts to rescue Americans held in Iran by Islamic radicals—resulted from sheer misfortune or Carter's miscalculations. One fact about the 39th presidency, however, falls unquestionably into the unlucky category. Carter will go down in history as one of only four presidents (including William Henry Harrison, Zachary Taylor, Andrew Johnson) who did not have an opportunity to appoint a member of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Yet, indirectly, he is responsible for one of the high tribunal's most consequential members: Ruth Bader Ginsburg. In addition, his approach to populating the lower federal courts with diverse judges reshaped the country's bench.

Carter's upbringing in rural southern Georgia impressed upon him life-long lessons about race and gender. His mother's independence as a nurse who ignored many of the Jim Crow South's racial segregation customs, and his exposure to Black playmates, clerics and, neighboring sharecroppers, formed his eventual embrace of equal opportunity for all Americans. Carter's career in the nuclear Navy coincided with President Harry Truman's abolition of racial segregation in the American military. By the early 1970s, he had fully embraced the modern civil rights agenda.

Standing for office in the Peach State, rife with traditional white segregationist politicians, Carter ultimately represented the more progressive New South. As his political career expanded, Carter's wife, Rosalynn, embraced an equal role with him in running their peanut farming business.

Once in the governor's office, the future president quickly changed the complexion of the state workforce, placing Blacks in 40 percent of influential positions, including boosting their number on Georgia boards from three to 53 and appointing the first Black state patrolman. African Americans rewarded him by casting their votes for Carter in 1976, catapulting him from "Jimmy Who?" to the Democratic presidential nomination and then on to the White House, with 83 percent of their ballots in the general election.

Carter's commitment to egalitarianism on matters of race and gender manifested itself in his approach to federal court nominations. He developed an affirmative action plan for the trial courts and courts of appeals. Long a bastion of white males, the 94 district courts and 13 courts of appeals form the core of the federal judicial structure. Distributed among 12 geographic clusters of states and the District of Columbia, plus one national circuit, the courts of appeals hear the vast majority of cases from the federal trial courts. All litigants have the right to appeal a loss from the district courts, and, because the Supreme Court's docket is discretionary and contains fewer than 100 cases a term, the courts of appeals are the last stop for all but a few cases.

Thus, Carter's 262 nominations to the federal benches, a record number at the time, guided by an effort to balance the representative characteristics of appointees, especially in terms of race, ethnicity, and gender, gave him an influential role in shaping the national judiciary.

His first year in office (1977), Carter established his Circuit Court Nominating Commissions and met with them in the White House to gather names of qualified women and minorities for the federal benches. This unprecedented process resulted in his naming 57 minority judges and 41 female jurists, numbers that exceeded the total of all previous presidents' minority and women nominees. He appointed nine Black people to the circuit courts (including Amalya Kearse, the first female African-American federal appellate court judge) and 28 Black jurists to the district courts. The 1978 Omnibus Judgeship Act, which created 152 new federal judgeships, aided Carter's record performance in Black appointments.

His most lasting impact resulted from his 1980 nomination of Ginsburg to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, a proving ground for Supreme Court justices. Ginsburg had served as the director of the American Civil Liberties Union's Women's Rights Project, during which she argued a half-dozen gender-equity cases before the U.S. Supreme Court and won all but one. Her scholarship as a tenured Columbia Law School professor and her successful advocacy for equality between the sexes caught Carter's attention.

Likewise, her compelling life story captured President Bill Clinton's imagination in 1993 when Justice Byron White retired from the nation's highest tribunal. In announcing her nomination, Clinton declared that Ginsburg was "to the women's movement what Thurgood Marshall was to the movement for the rights of African Americans."

If Carter had secured a second term in the 1980 election, it is likely that he would have had the distinction of placing the first woman on the high court. But that landmark belongs to President Ronald Reagan. Joining Sandra Day O'Connor as only the second woman to become a member of the court, Ginsburg played a historic role, especially in continuing her crusade for gender equity. She penned the court's opinion in the decision requiring Virginia Military Institute to admit women. Her dissent in the Lilly Ledbetter case successfully encouraged Congress to amend the 1964 Civil Rights Act's limits on when the victims of wage discrimination could challenge their employers in federal court.

Until her 2020 death, Ginsburg continued to fulfill the egalitarian agenda of Carter's post-Watergate presidency. She provided votes and authored opinions upholding access to abortion, allowing universities to maintain affirmative action policies in college and law school admissions, advocating marriage equality, and bolstering sexual privacy.

And RBG might never have made history on the nation's highest court without the 39th president's nomination of her to the second most powerful tribunal in the nation.

Barbara A. Perry(@BarbaraPerryUVA) is the J. Wilson Newman Professor of Governance and co-chair of the Presidential Oral History Program at the University of Virginia's Miller Center. She was a 1994-95 Supreme Court Fellow.

The views expressed in this article are the writer's own.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·