The terrorist attack in New Orleans on Jan. 1—and a truck explosion in Las Vegas just a few hours later that also seems to have had a political motive—are a reminder that extremist threats to our nation and our communities remain pressing, even as the landscape of terrorism itself is changing. The attacks also serve as a warning about the need for our counterterrorism strategies to evolve more quickly to adapt to these changes.

The traditional landscape of U.S. terrorism and extremism falls into two categories: international extremism, made up mostly of ISIS and al-Qaeda groups and affiliates, and domestic extremism, which includes white supremacist extremists, animal rights and environmental extremists, and a wide range of antigovernment extremists, such as unlawful militias, anarchists, antifascists, and sovereign citizens, alongside a large catch-all category called "all other domestic terrorism threats," which includes extremism motivated by gender, sexual orientation, and religion.

Islamist terrorism, which dominated U.S. security concerns for nearly 20 years after 9/11, remains a consistent threat. But by far the bigger national security threat now comes from domestic violent extremists, especially white supremacist extremists and antigovernment extremists, who are identified in an October 2020 threat assessment from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security as reflecting the most pressing and lethal threat to the homeland.

Two major changes in the terrorism landscape are driving much of the violence we see today. First, we have seen a shift from group-centered terrorism to lone-actor violence like the vehicle-ramming attack from the New Orleans terrorist. Groups still produce much of the propaganda and the playbooks that radicalize and mobilize people, introducing them to extreme and violent ideas and teaching tactics and strategies like weapons and explosive construction. But the vast majority of terrorist actors in the U.S. today are not part of an operationally networked group with a chain of command or instructions from a cell leader. Instead, they work alone, assembling weapons and planning strategies outside of the bounds of any group.

Second, the ideologies that motivate those violent actors have become broader and more diverse. In chat rooms and online gaming platforms, in comment sections and in influencers' video content, people encounter disparate bits of ideology and piece them together in new ways. The 2019 El Paso terrorist who killed 23 people at a Walmart was a white supremacist and eco-fascist, for example—using environmental justifications about climate change to argue that there will not be enough space for white people.

In other cases, the ideology is less central than the tactic of violence itself. In mid-December, the FBI seized the largest cache of explosive devices in history, finding more than 150 finished pipe bombs at the home of a Virginia man who is a member of a nihilistic, far-right group called "No Lives Matter." The group espouses accelerationism, which is a tactic that calls on mass violence, targeted attacks, animal abuse, and other harm to try to collapse social, political, and economic systems through civil-war-like violent chaos.

Extremist groups and movements like "No Lives Matter" often lack a clear ideology in the same way as a white supremacist or Islamic State group does. Instead, their aim is to disrupt social norms and values, desensitize followers to abuse and violence, and accelerate what they believe is a coming end-times collapse of civilization.

The problem of terrorist violence in the United States also suffers from broader mainstream support for political violence and willingness to engage in it, which has spiked across the political spectrum. After the recent assassination of a health care CEO, there was widespread celebration of an act of vigilantism that was lauded as 'just deserts' in ways that revealed how strong the "simmering anger" at the health insurance industry is across much of the population.

All of these changes make it harder to prevent mass or targeted violence with what have been our traditional strengths in counterterrorism work—such as surveillance, monitoring, infiltration, and interruption of plots. Adding more security measures to protect soft targets is expensive and ultimately still relies on a "just in the nick of time" dynamic to ensure community safety.

The only alternative is to shift our prevention work upstream, working to prevent people from being persuaded by propaganda and conspiracy theories to begin with and address the root causes that lead people down those rabbit holes to begin with. This includes addressing what so many terrorists ultimately express as a belief that they are enacting some sort of honorable quest that helps them find meaning and a sense of purpose.

Until we can ensure that every individual feels needed and that they belong, we will always have individuals who are vulnerable to bad actors who offer that instead.

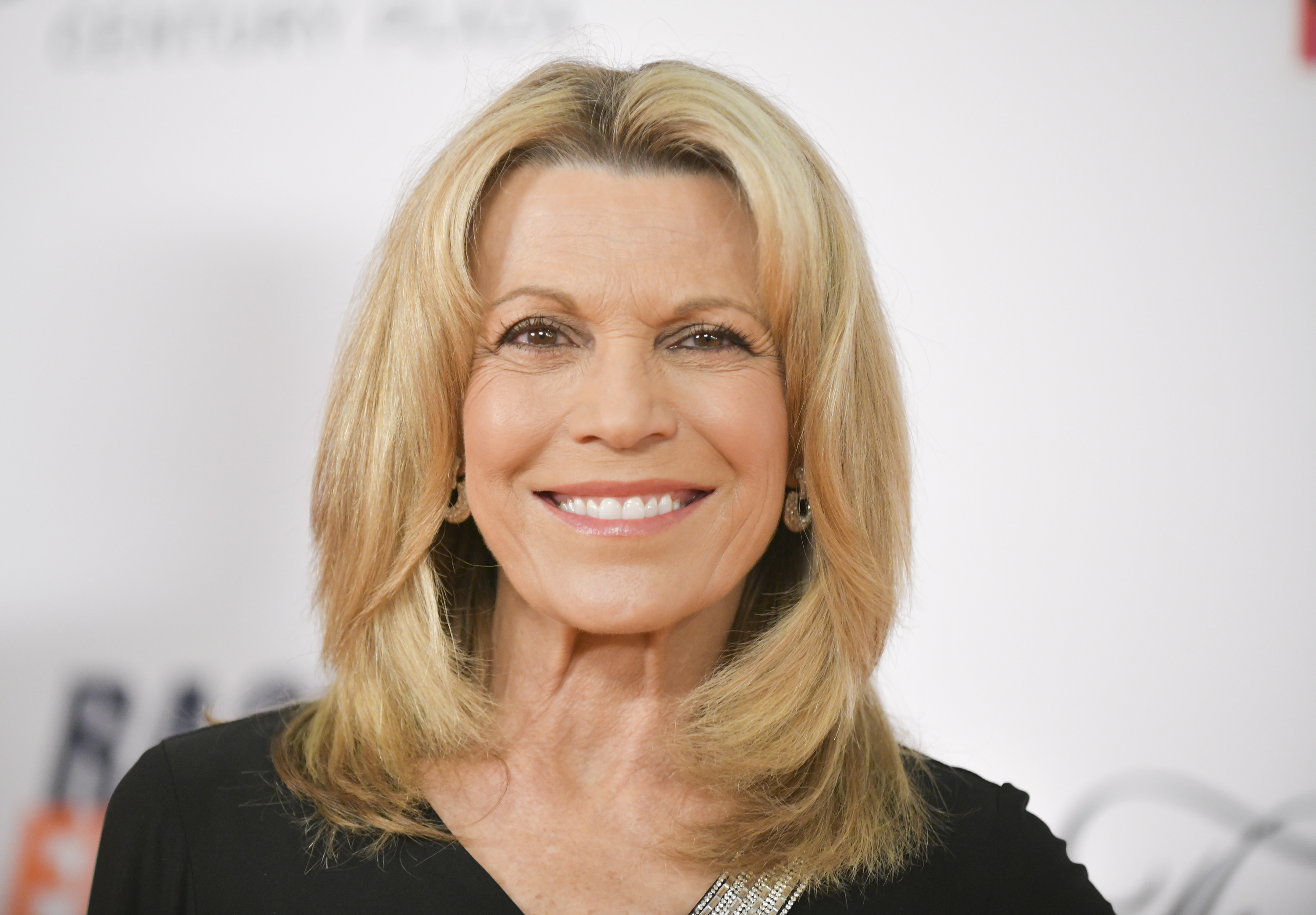

Cynthia Miller-Idriss is a professor at American University, where she leads the Polarization and Extremism Research and Innovation Lab (PERIL). She is the author of Hate in the Homeland: The New Global Far Right (2022) and Man Up: The New Misogyny and the Rise of Violent Extremism (forthcoming in 2025).

The views expressed in this article are the writer's own.

.png)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·