My father, Albert Garland, was born on December 6, 1926, in Brooklyn, NY, to a hardworking, middle-class family. He had two sisters and a brother. After graduating high school, he attended City College and then joined the U.S. Army, where he was stationed in Italy. After leaving the service, he entered the family poultry business to open a second location. The first was managed by my uncle and grandfather in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, and his location was on Delancey Street in the Lower East Side of Manhattan.

My dad was a man of many talents—intelligent, fluent in multiple languages, business-savvy, witty with a dry sense of humor, religious in his own way, and very charitable.

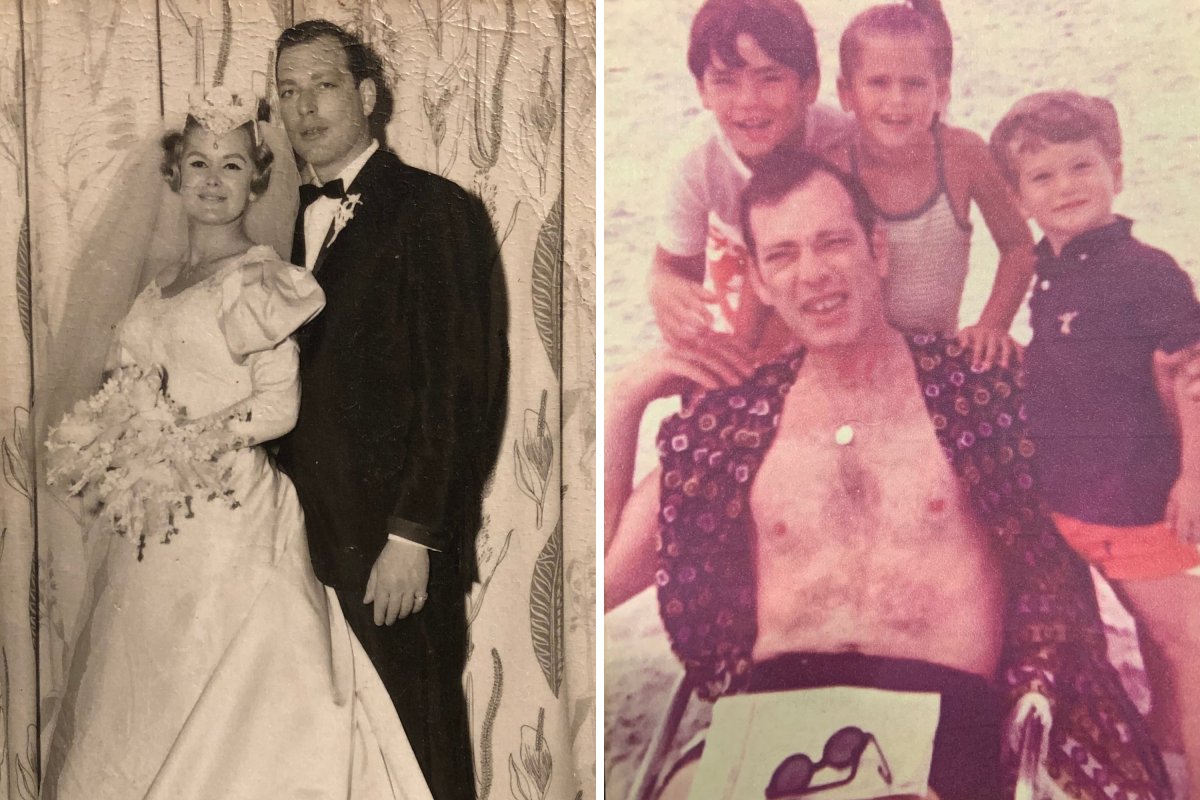

My mom and dad married in 1960 and started a family in New York City. A little while after my sister was born and my brother was on the way, we moved out of the city to Long Beach—about an hour outside of Manhattan in 1966.

We were a typical family of five living in the suburbs of Long Island. Life was good, and we were finding our way with three kids in their teens, doing what families do. Our father worked long hours—six days a week, commuting three-plus hours a day—to provide a better quality of life for us while mom maintained the household and everything that went with it.

On Monday, August 22, 1983, I had the day off from work. My brother was on summer break from high school, and my sister was preparing for her freshman year of college out of state. Mom was doing house chores and prepping lunch while Dad was at work in "the city."

My brother and I went to the park and had a very competitive tennis match— which I believe he let me win. Later, while enjoying a nap, I awoke with a severe headache unlike anything I had ever experienced. Minutes later, the phone rang. It was the owner of the auto body shop across the street from my father's store. He asked to speak with my mom in a tone that was very different from previous conversations. My brother and I sometimes worked with our father, and the shop owner was our Delancey Street neighbor.

I refused to hand over the phone, demanding to know what was going on. He finally told me there had been "an accident" and that our mother needed to get there quickly. I drove her into the city, and as we looked down from the Williamsburg Bridge, I saw NYPD and a crime scene. I knew. I tried to prepare my mother as we arrived on the scene.

Making our way through a crowd of over 60 onlookers, we were met by homicide detectives who gave us the news. I had to identify my father and insisted NYPD keep my mom outside—with good reason.

My father—husband, brother, Uncle Al, Big Al—was on the floor in a pool of blood, shot in the back, dead on arrival. As a fireman/paramedic, I had seen scenes like this before, but this was my dad. I immediately disconnected from the horror and went into task mode. We were escorted a block away to the 7th Precinct homicide unit, where we were questioned for about an hour before going home to deliver the terrible news to my siblings and extended family.

After notifying family—most painfully my younger sister and brother—we began funeral planning. This was delayed because, by New York State law, the Medical Examiner had to release the body after their examination. News and media outlets wanted the story, but we rejected their requests in our shock—a decision I now regret, as it might have brought forward information or witnesses.

After the funeral, we tried to keep the business running, but it didn't work out. The store was eventually sold. During this time, the lead detective, JC, would stop by with updates and to check on us, as we were a block from his office. Eventually, Detective JC was transferred. My sister left for college, and my brother returned to high school.

I took on the mission of seeking justice and finding out why this happened. Over 41 years later, I've failed. As the oldest child, I took every step possible:

Meeting regularly with detectives for updates and offering assistance, posting reward flyers throughout the neighborhood and increasing reward amounts, partnering with Crime Stoppers for TV segments reenacting the crime and promoting the reward—three times over five years, appearing on the Sally Jesse Raphael talk show, requesting help from The Vidocq Society, a nonprofit cold-case group—which NYPD rejected three times, maintaining communication with the NYPD cold case squad—though it was dissolved and later reinstated, and engaging with the NYC District Attorney's office, which recently shared a theory about what they believe happened and by whom.

Despite these efforts, justice remains elusive. My father's murder—of an honest, hardworking man—did not receive the attention warranted. A New York City official even apologized off the record for the "raw deal" we received.

My mother, now 94 and in a nursing home, still asks about the case despite her declining cognition. The rest of my family has mostly let it go. Yet, I cannot stop pursuing answers. Shows about cold cases solved with new technology or witnesses speaking up give me hope.

The pain remains, but after all these years, it's likely the killers have met their maker. Still, I hope that one day, before my time comes, the momentum will yield answers.

Gordon Garland is a 64-year-old father of two girls. He works in healthcare in Florida, having left New York roughly 25 years ago.

All views expressed are the author's own.

Do you have a unique experience or personal story to share? See our Reader Submissions Guide and then email the My Turn team at myturn@newsweek.com.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·