By Anthony N. Galanos

This is so easy to write and yet so terribly difficult.

Easy, because every grieving parent is most likely thinking of their child who died most if not all day.

So hard, because we know we speak our own language and that so many people, despite how well-intentioned, might think my thoughts strange or surprising.

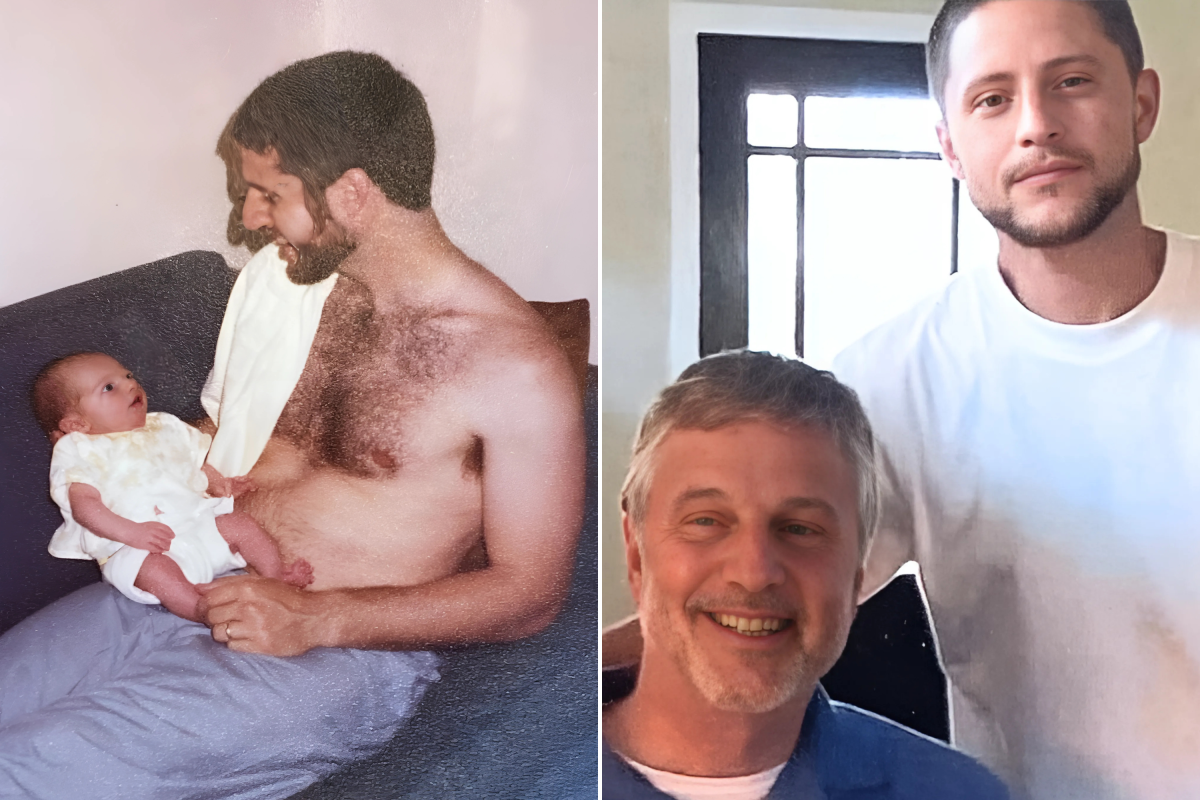

Add to this that Nick was 34 years of age, not a child, and you get that extra layer of not understanding a loss after six years.

I have had "anticipatory" grief ever since Nick was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes, meaning insulin requiring, at age eight.

As an internal medicine doc, I tried to stay so hard in the "dad lane," but the moment that the young doctor told Nick and me that it was "diabetes", I began crying uncontrollably. I was worried about the finger sticks, the diet and, most of all, his life expectancy.

His mom was so much better at the adjustment required than his overeducated dad. His mom was able to do what was required all the while with a loving and sensitive demeanor.

After about six to eight weeks of diabetes management, Nick magically said to us: "I tried it and I don't like it. I don't want to have diabetes anymore."

That broke my heart and I was almost grateful for the magical thinking that an eight-year-old can employ. It was at night, upstairs, and I remember exactly where I was standing when Nick spoke those words.

A year goes by and his five-year-old little sister, Rachel, develops Type 1 also. I went out into the driveway and cursed God, and then begged God to give me something awful so that Nick and Rachel would be spared.

I still wish that there were a trading store somewhere where folks better equipped for an illness can accept the burden from one of their family, like donating a kidney or being a match for bone marrow. Think how busy that "trading store" would be because of the willingness of parents to sacrifice for their children.

But as Rabbi Kushner put it in 1981, suffering is not evenly distributed and sometimes bad things happen to good people, or certainly innocent ones, like children.

We were fortunate to be at Duke, where there was an entire division of pediatric endocrinologists. And we were fortunate that Rachel's diabetes from the get-go was a bit more manageable than Nick's labile journey.

I still bristle when a well-intentioned person asks me if Nick had been a "good diabetic".

Again, alluding to Kushner's book, When Bad Things Happen to Good People, people try to make sense of the world and one way to do that is to believe that whatever happens to a child, they somehow deserved it.

Please understand and share that Type 1 is a disease and not a moral flaw. And that the genetic underpinnings are becoming better and better known. And Nick's disease was always so much more labile and difficult to manage.

Probably because of Nick, we diagnosed Rachel's Type 1 without an episode of diabetic ketoacidosis, and we were much more calm and better managers of Rachel's journey than Nick's.

I don't know for sure that he ever appreciated what he did for Rachel and us in that regard. And I hope somehow he can feel our love. What parent does not want or wish that?

Nick died in September 2018, at the age of 34. We recently acknowledged and honored his anniversary.

He died of diabetic ketoacidosis following a viral illness that caused nausea and vomiting and sent him into ketosis—a condition that can make our blood acidic and even stop the heart.

Being a middle child, a Greek, and a doctor, I made up the word "gruilt" to help me absorb the blow of his death.

Gruilt is 80 percent pure, white-boned grief, with 10-20 percent of guilt. Reading the "parental grief "academic literature, you will find the word "guilt" in the title of many published articles.

It has been six years, and I still go over the tape and ask myself what I could have done differently.

In the early days of "acute grief", my nerves were out on my skin, and I cried daily—almost always alone. This resulted in eating too much, the Greek response to stress, and a sleep disturbance that has been recalcitrant to all kinds of interventions.

I read one article where the dads had sleep problems out to nine years after their child died, and we don't know how much longer that goes on because that was the end of the study.

Which brings me to the most important point: There is no timetable, there is no time that a parent will "get over" the death or will "move on". There is a time, in fact, when a parent can learn to accommodate the loss, not accept it, and return to work and social relationships.

But there is NOT a time when we should expect someone to forget their child died or endorse the sentiment of "shouldn't you be over this by now?"

I think most grieving parents could write a book, if not several articles, on what NOT to say to a grieving parent. This is not part of medical, nursing, or PA schools, so I hope my friends in the mental health fields are learning this as part of their curricula. I have my doubts.

Not all stories have to have a happy ending, and not all sadness has to have meaning. The wonderful writer Megan Devine has written that "... acknowledgment is the only real medicine for grief" and we cannot fix the unfixable.

So, I have learned to carry my grief, Nick's mom and sister carry their grief in their own way, too.

My morning prayers always include peace on earth, blessings upon both children and at the conclusion: "I pray for the strength to carry my grief and to teach grief to others."

I am still Nick's dad, and we parents are still the parents of the children who died. And as long as we love our children, we will grieve them.

Grieve well, my fellow parents.

Anthony N. Galanos MD is a professor of medicine at Duke University.

All views expressed are the author's own.

This essay was produced in partnership with Evermore, a national nonpartisan nonprofit dedicated to making the world a more livable place for all bereaved people.

Do you have a unique experience or personal story to share? See our Reader Submissions Guide and then email the My Turn team at myturn@newsweek.com.

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/04/24/878/n/3019466/36c5693c662965c5d1ce91.72473705_.jpg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·