A study on the teeth of ancestors to humans that lived around 3.5 million years ago has found they were mostly or totally vegetarian.

The consumption of animal foods such as meat is considered to be a crucial turning point in human evolution, that archaeologists link to the growth of the brain and the ability of pre-humans to make and use tools.

But evidence of when prehistoric people started eating meat has been difficult to find.

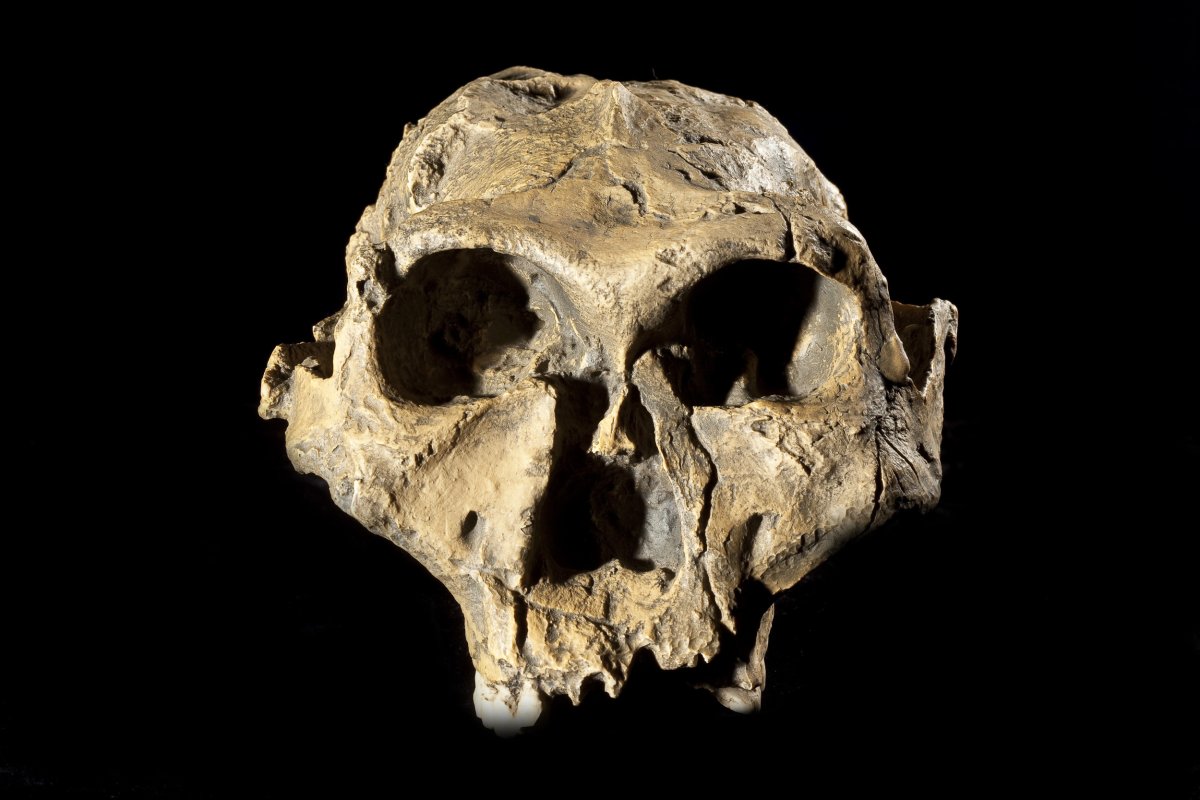

Australopithecus was a hominin—a human-like mammal—that walked on two legs but had smaller brains than Neanderthals and modern humans.

In this study, scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Germany and the University of Witswatersrand (Wits) in South Africa analyzed different versions of nitrogen present in the fossilized tooth enamel of seven Australopithecus individuals found in southern Africa.

Analyzing nitrogen isotopes—different forms of nitrogen that might be heavier or lighter depending on the neutrons in its nucleus—can help archaeologists understand an animal's place in the food chain.

When animals digest food, their bodies tend to use and get rid of more of a lighter form of nitrogen, called 14N, through their urine, feces and sweat, leaving behind more of a heavier form of nitrogen, called 15N, in their bodies when compared to the food they eat.

This means that plants contain a lot of 14N but not much 15N; herbivores have more 15N and less 14N in their bodies than the plants they eat; and carnivores have a lot of 15N and not much 14N.

So, the more 15N an animal has in its body compared to 14N, the higher up in the food chain it is believed to be.

Nitrogen isotope ratios have long been used to study the diets of modern diets and humans, for instance from their hair and bones, but this is difficult to do in very old fossils because of how materials degrade over time.

But this team of scientists used a new technique developed by the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry to measure nitrogen isotope ratios in fossilized tooth enamel that is millions of years old.

"Tooth enamel is the hardest tissue of the mammalian body and can preserve the isotopic fingerprint of an animal's diet for millions of years," said geochemist Tina Lüdecke, lead author of the study from Max Planck, in a statement.

Lüdecke and her team analyzed isotope data from the tooth enamel of Australopithecus individuals found in the Sterkfontein cave near Johannesburg, South Africa; an area known for its collection of early hominins fossils.

They compared it to isotopic data from tooth samples of coexisting animals, such as monkeys, antelopes and hyenas, to work out where Australopithecus fit in the prehistoric food chain.

They discovered no evidence of meat consumption; Australopithecus ate a varied plant-based diet, perhaps with occasional consumption of eggs or termites, but that was broadly vegan.

Lüdecke's team plans to expand their research to explore when meat consumption began among hominins, how it evolved and whether it helped our ancestors.

Alfredo Martínez-García, from the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, said in a statement: "This method opens up exciting possibilities for understanding human evolution, and it has the potential to answer crucial questions, for example, when did our ancestors begin to incorporate meat in their diet? And was the onset of meat consumption linked to an increase in brain volume?"

This study was published on Thursday January 16 in the scientific journal Science.

Do you have a tip on a food story that Newsweek should be covering? Is there a nutrition concern that's worrying you? Let us know via science@newsweek.com. We can ask experts for advice, and your story could be featured in Newsweek.

Reference

Lüdecke, T., Leichliter, J. N., Stratford, D., Sigman, D. M., Vonhof, H., Haug, G. H., Bamford, M. K., Martínez-García, A. (2025). Australopithecus at Sterkfontein did not consume substantial mammalian meat, Science, 387(6731). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adq7315

English (US) ·

English (US) ·