Sean Baker‘s “Anora” is a wild and moving movie, a skewed fairy tale that veers from slapstick comedy and romance to action and tragedy, hitting every other tone on the emotional scale along the way. Yet Baker didn’t want a traditional score — there’s no music that isn’t source (predominantly the needle drops in the strip club where Mikey Madison‘s title character works), and thus none of the typical clues to guide the audience’s responses to the tonal shifts.

That created a challenge for sound designers, supervising sound editors, and re-recording mixers John Warrin and Andy Hay, whose sound environments had to serve the function that music would in a more conventional film. “It leads to a situation where sound design often behaves as score,” Hay told IndieWire. “Texturally, emotionally, what are we trying to say in any given moment? That leads us to various decisions.”

The final scene in “Anora” is a case in point. Without giving too much away, it’s an emotionally devastating moment in an old Mercedes where the weight of everything that has happened in the film finally comes crashing down on the protagonist. While Madison’s performance in the scene (and the film as a whole) has been justly celebrated, there’s a whole other layer of emotional effect that comes not from how the moment is acted and shot, but how it sounds.

Warrin and Hay treated the various sounds of the Mercedes as instruments to be orchestrated, starting with the windshield wipers. “The windshield wipers that were recorded on the day was going through its own sonic arc based on the amount of snowfall,” Hay said. “It starts off dry and squeaky and mechanical and irritating. Then over time, it turns into a sort of whisper and has a gentle nature. We keyed into that and it inspired a concept for how we could score that scene with sound design.”

Warrin and Hay carefully reconstructed the rhythm of the wipers to convey what they needed to about Ani’s emotional journey, something that was made trickier by Baker’s insistence on absolute realism. “We can’t use the tools for really weird sound design stuff, because that’s just not going to work with the style of the movie,” Warrin told IndieWire. “We’re trying to be as realistic as possible, so that means we’re using real sounds in the environment and creating our arc from that.”

Warrin says that the sound department played not only with the tempo of the windshield wipers, but also the engine itself, which didn’t have a steady hum but a kind of rattle that could be adjusted to increase and decrease agitation. The filmmakers also brought in squeaks from the seats that came from the production sound and made them part of the sonic orchestration. “We played around with where to place each squeak,” Warrin said. “We spent a fair amount of time pulling out certain squeaks with Sean sitting behind us, working out the tempo with the engine and the wipers.”

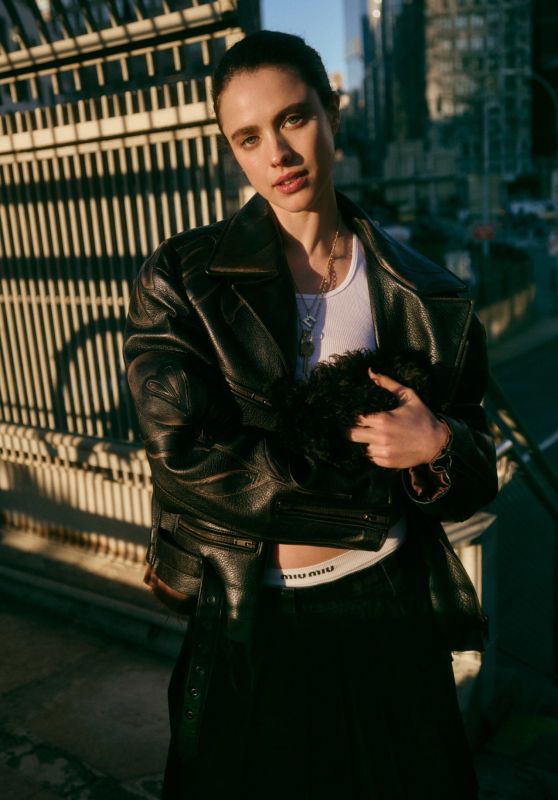

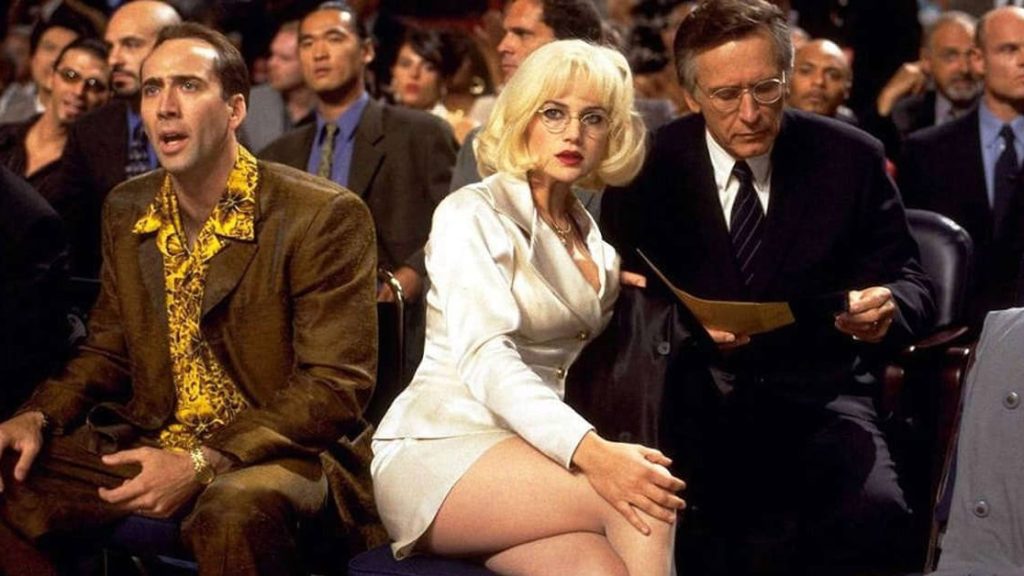

‘Anora’Courtesy Everett Collection

‘Anora’Courtesy Everett CollectionBaker’s insistence on realism also guided the sound design of the scenes set in HQ, the club where Ani works. While “Anora” doesn’t have score, it does have a lot of music in the form of needle drops that play in the club, and Warrin and Hay were careful to modify its sound depending on which area of the enormous club is on screen at any given moment, as well as on the emotional requirements of each specific scene. To do that, they had to create a map of the geography of HQ.

“We made a map to know where each room is in reference to the main floor so that then was can all talk intelligently about why one room would sound different than another and how it would differ,” Hay said. “It’s a strip club, and the music needs to be loud and it needs to feel like a place that is super busy with a ton of people.” The actors projected loudly enough in their dialogue for the filmmakers to convincingly play the music as loud as possible, and Hay used the map of the club’s space to think about where speakers would be placed and what sort of quality they might have.

“Are they new, are they old, does this one have a blown out tweeter, so on and so forth,” Hay said, noting that he borrowed an idea from “The Social Network” mixer Michael Semanick. “In that film, he very much played with different speakers within the space, so I took a page out of that script and tried to emulate the same thing with a lot of work going into what’s playing where and how much bleed from one room is bleeding into the next. So we establish that musically, and then John works in the crowd to match, and we work in a little bit of loop group to give us some sort of foreground life.”

While Hay says that dialogue is always key, it was also important not to let the music fall into the background. “What is it about this particular music track that is identifiable? Why this track? Is it the bass line? Is it the vocal element, or a melodic line? So we’re trying to retain enough for the track to be identifiable but then sacrificing other elements of the track so the dialogue can play.” Finding that balance while adhering to Baker’s mandate for realism led to a club that Hay calls “bumpin’ and loud and, at times, obnoxious. It’s a really fun, creative mixing challenge to play with all of that.”

English (US) ·

English (US) ·