Between the end of the ’60s and the turn of the ’70s, onscreen heroes who could save the day fizzled out in popularity. Many films were either staunchly liberal or left-wing, from “The Battle of Algiers” (1966) to “Z” (1969) and “The Confession” (1970), with protagonists as victims of fascist right-wing regimes. Films with heavy-hearted themes opened audiences’ eyes by examining the victims and consequences of these systems. It seemed conservatives were missing a hero to affirm and spread the message of their misunderstood beliefs and principles. Enter: Dirty Harry.

Harry Callahan, played by the blueprint of ideal male masculinity, Clint Eastwood, took control and got stuff done on his own terms. He challenged an entire nation’s political and moral compass. A police inspector working in the heart of San Francisco, one of the most liberal states in America, puts an end to the real perpetrators of crimes committed in the homeland — hippies! Or, to put it more favorably, the left, and their systems and institutions. The criminal in the story is called Scorpio, who acts as a counterpoint to Harry’s views. He also reinforces the stereotypes associated with the leftist counterculture movement of that era — long hair, unkempt, violent, exploitative of the law, nihilistic, etc. He is portrayed as morally bankrupt and the reason for senseless violence and evil within America. Some audiences saw this as a warning, linking the societal shifts and movements of people aligned with the left as dangerous and uncouth. Of course, people on the left would understandably deny that they align with Scorpio at all and say that Scorpio is nothing but a tool for propaganda.

The film divided critics as well. Even those against the film’s message gave props to its skillful filmmaking and suspenseful scenes, but critic Pauline Kael described it as a “gestapo movie,” referring to the secret Nazi police in German-occupied Europe. Critic Roger Ebert gave a mixed review, applauding its relevance but not necessarily agreeing with it, calling it a “mirror of society.” Audiences seemed to love it when it came out; it became a pop culture hit. It’s certainly not remembered as a fascist film these days. It has extremely favorable ratings and reviews on film websites nowadays, and if you ask anyone about the film, they won’t talk about its politics, but rather how awesome Clint Eastwood is with his Magnum .44 and his unforgiving, stoic attitude. Of course, there are still some reviewers today who hold onto the belief that “Dirty Harry” is nothing but propaganda.

Harry puts it simply in quotes like: “Nothing wrong with shooting, as long as the right people get shot,” and “Well, I’m all broken up about that man’s rights.” Harry has his beliefs, and he’s not going to allow these stupid rules and regulations to limit his ability to achieve justice, even if it means losing his job. Ask yourself a question: If you knew someone was guilty of murder and would get away with it, would you step outside the rules to make sure that son of a bitch gets a taste of justice? Harry Callahan certainly thinks so.

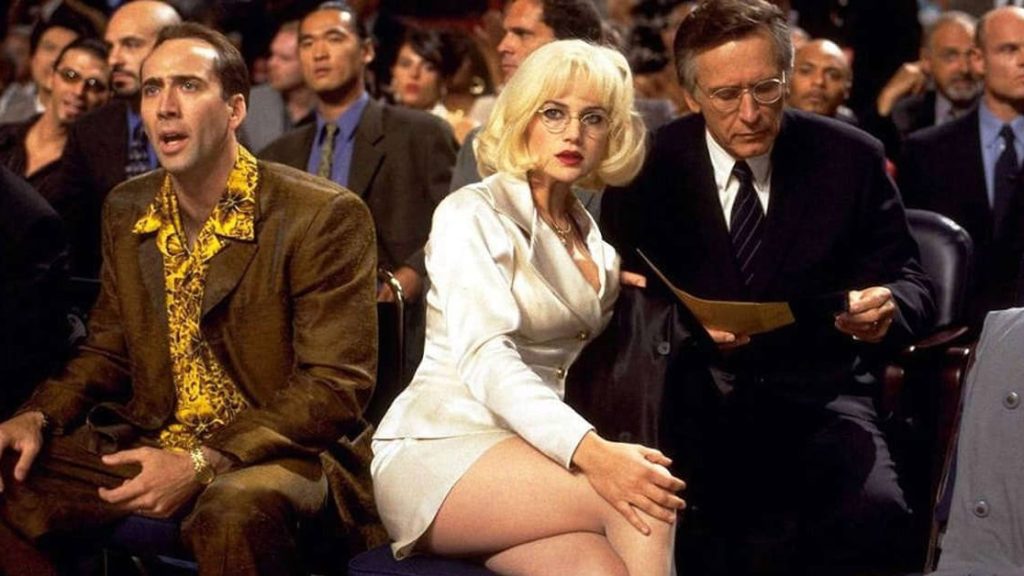

‘Dirty Harry’©Warner Bros/Courtesy Everett Collection

‘Dirty Harry’©Warner Bros/Courtesy Everett CollectionThe film itself is a masterful, thrilling cop movie, but at its core, “Dirty Harry” critiques the rules and regulations of the justice system. Ask yourself another question: Why should a murderous, sadistic criminal be entitled to rights that keep them out of jail when they’re a murderous, sadistic criminal? I’m not implying an answer here — it’s your job to answer the question or even dismiss it as illogical. But just know that Harry thinks of these criminals as animals, meaning he doesn’t give a darn about their rights.

What was director Don Siegel and writers Harry and R.M. Fink’s motivation in making a movie that shows a badass and mythical character solving the flaws of a current system? If we’re responding to Kael, was it fascistic? Was it to genuinely display how police and justice systems should function in our world? If so, then yes, this film supports fascism in one way or another. But in a 1972 interview with Don Siegel for The New York Times, he said, “I’m a liberal; I lean to the left. Clint is a conservative; he leans to the right. At no point in making the film did we ever talk politics. I don’t make political movies.”

So there you have it. Pauline Kael can calm down now. “Dirty Harry” is certainly a superbly entertaining film about a cool cop working in a system with rules that should be questioned as to whether they need to be bent at times. But Siegel later goes on to explain that he resents authority, so it’s impossible to truly know what he intended and didn’t — though perhaps it no longer matters. Either way, Siegel does not have the authority to say that this film isn’t political. In this medium, whatever the audience interprets automatically makes them correct.

The discussion will continue around “Dirty Harry’s” politics, whether intentionally incorporated into the film or not. What can’t be doubted is that the sequels most definitely leaned into the idea that Harry Callahan symbolizes a political stance or belief system. Was this due to the producers and writers capitalizing on the audience’s reactions and the buzz it created, or was the character Harry Callahan always a symbol of that belief system? That’s another question you’ll have to ask yourself.

Now I know I’m asking a lot of questions here, but I need you to ask yourself one more: Do ya feel lucky, punk?

English (US) ·

English (US) ·