Given the many distracting ongoing wars around the globe currently, geopolitical experts worry that China may seize the opportunity to take over Taiwan, a former province of China, which Beijing insists is part of "One China." The invasion of Taiwan—an economic powerhouse where over 90 percent of the world's superconductors are produced—would set off a global chain reaction, explains Professor of Chinese Studies Kerry Brown in Why Taiwan Matters: A Short History of the Island That Will Dictate Our Future (St. Martin's). In this excerpt from his book, Brown shares the genesis of the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, which produces the "brains of modern electronics."

Hsinchu Science Park, southwest of Taipei, Taiwan, is not a scenic spot for tourists to wander around. But on days when the temperature is not so searing that it melts the soles of your shoes and drenches you in sweat if you step outside, or when there are no torrential rains or typhoons to send you scuttling back into the welcome shelter of a taxi, it has a certain kind of serene calm.

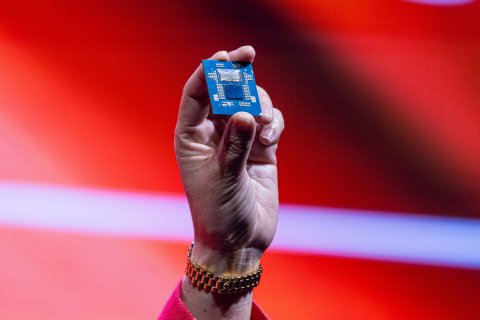

Science parks like Hsinchu are dotted across the world. They have a certain generic feel, with their box-like buildings mass-producing whatever they do to fill the global markets with goods. In 1987, this science park backed one particular winner. That windowless white monolith and the dark glass-clad block abutting it contain one of the world's most valuable companies, one responsible for 8 percent of Taiwan's overall economic output, and 12 percent of its exports. More than that, this place sits at the center of the global economy, a beating heart that pumps out the chips and semiconductors that power everything from coffee makers and drones, to smartphones and artificial intelligence systems. You may not know it, but you are more than likely to be carrying one of those chips right now in your pocket.

By 2023, the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company produced over 90 percent of the world's most advanced semiconductors, the critical components that power every computer. Without them—"the brains of modern electronics," as they have been called—there would be no smartphones, computers or advanced medical diagnostic equipment.

Were this a geopolitical thriller, the addition of this factor to the already complicated cross-strait situation between China and Taiwan would be regarded as a plot twist too far. For the dispute between them is not just a geopolitical matter, but a geoeconomic one, too. The "semiconductor wars," as they have come to be called, are a distinct but hugely significant element of this conundrum. It would be tempting to say that this was all in accordance with a deliberate strategic plan on Taiwan's part. But in the early phase of Taiwan's economic development, the aim was merely to be more self-sufficient, and to become a little bit wealthier. The day Hsinchu Science Park was founded, there were no neat blueprints for how economic success would have important national security implications. That was all to unfold later.

Taiwan's Early Development

The start was not auspicious. After the Nationalist creation of a separate government on the island in the late 1940s, there was precious little advanced industry. What did exist was the result of half a century of Japanese rule. Reasonable infrastructure was in place, with rail, road and functioning ports. War had not decimated this the way it had on the mainland, where the situation was far worse.

By the 1970s, Taiwan had become one of the Four Asian Tigers of the region (the others were Hong Kong, Singapore and South Korea). In concert with Japan and South Korea, it had entered the global economy by manufacturing and exporting goods and

components that had become too expensive, or too polluting, to make elsewhere. The markets of Europe and North America were the chief destination for the things it made. Taiwan's agriculture sector remained important, but in a country where most land was mountainous and unusable, high-value production was the key to future wealth creation.

Semiconductors offer a classic case study of how the process of state directed development in Taiwan worked. In the beginning, during the 1970s, the Taiwanese government's science and technology administration did not see this sector as a viable one. It was too capital intensive, demanding high levels of investment and financial support. The country did not possess the key technology, and therefore either needed to procure it from elsewhere or put significant resources into research and development to try to create it. There was inevitable reluctance by officials to considering entering an arena where the Japanese, Dutch and Americans seemed well ahead and would do everything they could to prevent competition.

Morris Chang was a key player in changing this situation, which was to have momentous consequences. Born in China in 1931, into a middle-class family, he left during the Communist takeover at the age of 18. In an interview in 2007, he recalled how "China was so poor, most of the people were so poor, even [the] middle class." The U.S., where he moved, "was a paradise when I first arrived," because of its social, political and educational advancement. A quarter of a century of service to Texas Instruments ended in the early 1980s with no new job lined up. But Chang had the rare combination of management skills and technological knowledge, which made him an attractive proposition for other companies and partners. It was understandable why Kwoh-ting Li, Minister without Portfolio in the Chiang Ching-kuo administration in the 1980s, targeted Chang. Li was a talent spotter; seeing the Chinese American at a loose end, he was an obvious figure to recruit. The new ethos in Taiwan took semiconductors seriously, and Chang seemed the perfect man to deliver something.

In the Museum of Innovation at TSMC in Hsinchu, located next to the building named after Chang today, there is an electronic copy of the first business plan he presented to the Taiwanese government, in 1987. It makes the case for what he wanted to do in very simple terms. There were four parts to the process of making semiconductors, as he saw it. First of all was development: IC board design and planning what needed to be made and why. Second was creating the technology to bring these products into existence. Third was the actual manufacturing of them. Finally, they needed to be sold to customers. Companies tended to try to do all of these stages. They'd come up with an idea, then have to invest in the means of making it, go through the production process and after that do the selling. But as technology advanced, it became clear that the levels of investment, and the ever-increasing specialization, meant it was harder and harder to do everything in-house.

Chang's proposal was that TSMC focus only on the second and third parts of the process (designing the machines to make the products and then manufacturing the chips). Its customers would be companies with an idea for a chip and what it could be used for. They'd bring that to Chang's new venture and agree on the best way of manufacturing it. TSMC then simply produced the chips for their client, who then went on to use them for whatever requirement they had. It did not deal with sales to end users such as consumers or smaller retailers. There are no TSMC-branded goods in the world, and yet probably every home has products with key components in them made by the company. Opting out of the first and final stages meant that massive focus was placed on producing the best processes and equipment for making chips and only chips.

A Race to Miniaturize

When you visit the factory, it is easy to see just what a challenge it is meeting the demands of this very specialist market. The sheer level of technology needed to make these products, and the massive amounts of capital and technical knowledge required, are astounding. A camera shows different parts of the chip-manufacturing process. Standing gazing at it all, I was overcome the sheer complexity of what was involved. Humans barely appeared on the factory floor. Almost impossible levels of cleanliness are required. Suspended from electronic rails on the ceiling, small robotic machines ran with an eerie, almost human purposefulness, sporadically dropping components down on extendable wires in order to add to whatever product was being made. These buildings, which are so simple and featureless on the outside, inside are a symphony of activity and constantly moving parts.

The relentless focus on being just a chipmaker meant that TSMC has been continuously profitable from 1991. By May 2024, it had become the ninth most valuable company in the world, with a market capitalization of $730 billion. In little more than a decade, it had increased its value tenfold. Chang served as the chief executive officer until 2005, and then a second time from 2009 to his full retirement in 2018. A self-effacing man, in an interview with the New York Times in 2023, then well into his 90s, he said that "I would rather stay relatively unknown." At the same time, he showed a clear awareness of what his contribution had brought to Taiwan. "I was literally sure that we had achieved technology leadership...I don't think we'll lose it."

Chang was also a major player in creating something that China clearly wanted. "We control all the choke points," he told the New York Times. "China can't really do anything if we want to choke them." Its dependence on TSMC technology is still high, despite many efforts to accelerate the growth of its indigenous industry. The problems, however, are as much technical as political. The semiconductor business is partly a race to the most miniature. The precision needed to produce the most advanced chips is staggering. So too are the supply chains. TSMC may be one principal source of the industry's best products. But it is dependent on an ecosystem where just one of the most advanced lasers used for producing the chips itself requires 457,329 separate components. Despite vast research and development funding, China still lags Taiwan by a decade or more. It seems to be perpetually chasing a mirage, its object forever receding from it.

Just how much of a security guarantee is this for the island? On that point, there is disagreement. According to one report, "When it comes to semiconductors, China needs Taiwan more than the other way around." But another perspective is simply that the presence of this incredibly valuable and important technology in a territory that China regards as its own only makes Beijing more anxious to take the island. "In the current scenario, TSMC's position makes China covet Taiwan even more," Wu Jieh-min at the Taiwanese research institute, Academia Sinica, was quoted as saying. This is particularly so in view of the increased U.S. investment in producing top-quality semiconductors back home. For all the talk by Taiwanese officials of the "silicon shield" protecting them, reliance on it as an absolute guarantee of the island's safety and security would be foolhardy. After all, an attack by China would not only smash its own source of supply but also those of everyone else. Lose-lose this might be; but in Beijing's eyes, at least, it doesn't cede any advantages to its competitors.

What the presence of TSMC does do is complicate an already complex situation. The scenario planners in foreign governments and international organizations need to factor into the mix not just the military and geopolitical fallout of conflict between China and Taiwan, but also the absolute certainty that it will wreak havoc on the global economy, if only because of the collapse in supply of this one profoundly important component.

▸ Adapted from Why Taiwan Matters. Copyright © 2025 Kerry Brown. Published by St. Martin's Press. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·