Despite widespread fears of a catastrophic "supervolcano" eruption, scientists at the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory (YVO) have suggested that any eruptive event there would likely look far different from the doomsday scenarios many envision.

Mark Stelten, deputy scientist-in-charge at the YVO, explained that while the idea of a "super-eruption"—which would spew catastrophic amounts of ash and lava across the country and beyond—is often sensationalized, such events are exceedingly rare.

The last super-eruption at Yellowstone occurred about 640,000 years ago, and the likelihood of another similar eruption in the near future is extremely low.

What an Eruption at Yellowstone Would Really Look Like

What might happen if Yellowstone were to erupt is difficult to predict with any certainty, though Stelten offered some insights into some of the more plausible scenarios.

Smaller eruptions, which are far more likely than a super-eruption, would likely produce lava flows or domes, which, although dramatic, would be less destructive and pose little threat to people.

"It could be a slowly moving lava flow that wouldn't endanger anyone too much as they could easily move out of the way," Stelten told Newsweek. "I'd suspect there would be potential for wildfires as the lavas erupt at high temperatures. Park roads and infrastructure could be compromised, but the effects away from Yellowstone would be minimal most likely."

Smaller eruptions have occurred over the last 160,000 years or so, with two of note within the crater, or Caldera, formed by previous super-eruptions.

"Sometimes these smaller eruptions can produce small calderas within Yellowstone caldera," Stelten said. "For example, the West Thumb of Yellowstone Lake is a caldera formed during an eruption 160,000 years ago, called the Tuff of Bluff Point."

Such smaller eruptions could be explosive too. While they may not send an umbrella cloud of ash across the U.S., such an event would still "create a sizeable ash cloud that may effect the local climate," Stelten said.

Warning Signs of an Eruption at Yellowstone

In the event of a volcanic eruption, scientists would be able to detect key warning signs well in advance.

Major eruptions, and even smaller ones, are preceded by significant geological activity, such as swarms of earthquakes and rapid ground uplift—movements that would alert scientists and provide critical time for monitoring and preparation.

"Yellowstone hasn't erupted for 70,000 years, so it's going to take some impressive earthquakes and ground uplift to get things started," the YVO says on its website.

"Besides intense earthquake swarms (with many earthquakes above M4 or M5) we expect rapid and notable uplift around the caldera (possibly tens of inches per year). Finally, rising magma will cause explosions from the boiling-temperature geothermal reservoirs."

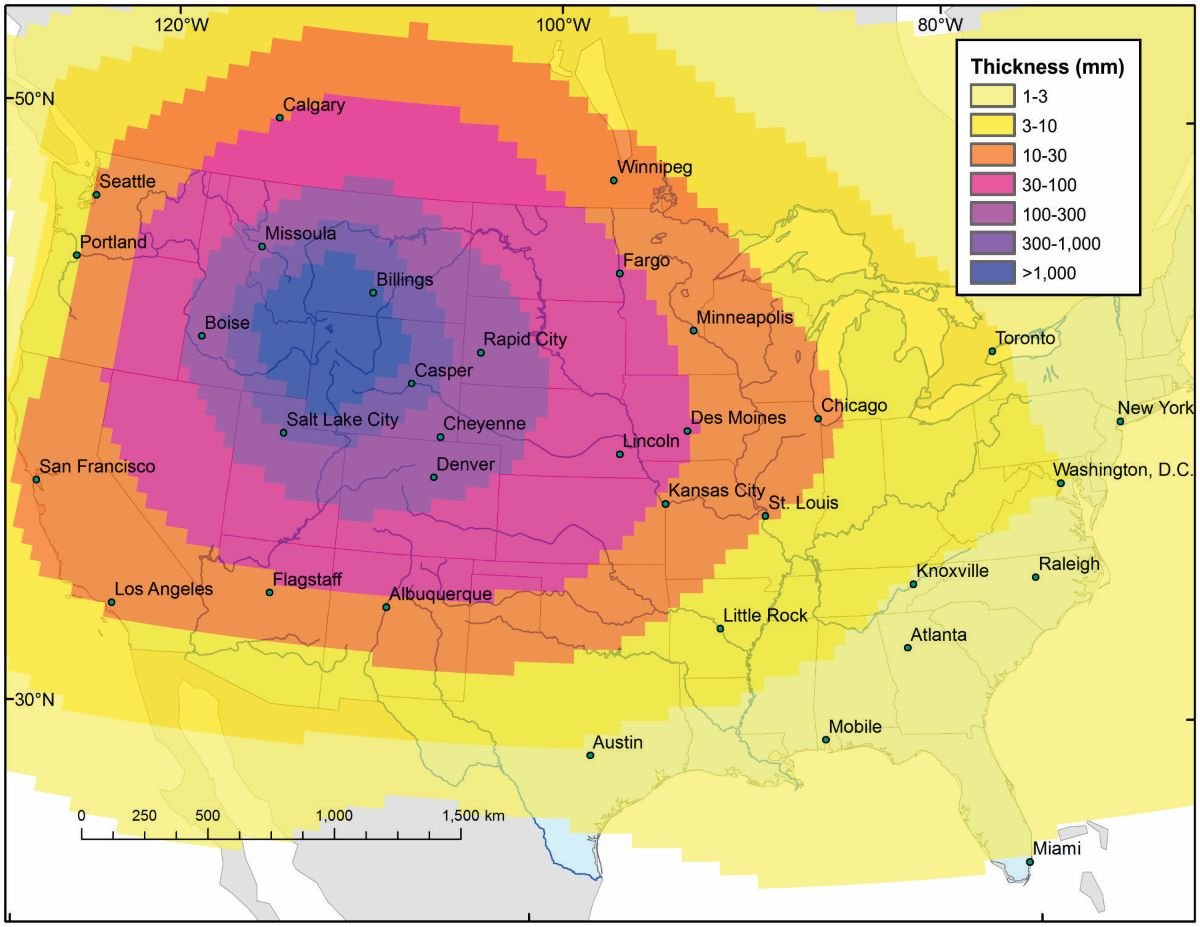

Ash Dispersion: Supervolcano vs. Smaller Eruptions

One of the biggest misunderstandings about Yellowstone eruptions is the potential for ash clouds. While a super-eruption would spread ash across thousands of miles, as shown in a 2014 study published in the scientific journal Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, smaller eruptions behave differently.

Ash from smaller eruptions would likely follow a more localized pattern, with ash falling primarily within Yellowstone and its immediate surroundings.

Should You Be Worried?

The YVO advises that members of the public be prepared for emergencies in general, but there is no reason to specifically fear an imminent volcanic eruption.

Since the last major eruption about 640,000 years ago, Yellowstone has remained essentially dormant and will likely continue to do so for some time. Although scientists continue to monitor the area closely, any future eruption is expected to follow the pattern of smaller, less catastrophic events, with minimal regional or continental impact.

For now, Yellowstone continues to captivate visitors and researchers alike with its geothermal beauty, rather than with any immediate threat of catastrophic eruption.

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about the Yellowstone supervolcano? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Reference

Mastin, L. G., Van Eaton, A. R., & Lowenstern, J. B. (2014). Modeling ash fall distribution from a Yellowstone supereruption. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 15(8), 3459–3475. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GC005469

English (US) ·

English (US) ·