Sony Pictures

American Movie is a painful watch. Usually that’s a dealbreaker. In the case of Chris Smith’s unflinching (but not unfeeling) 1999 documentary about Mark Borchart’s struggles to complete his 35-minute short Coven, it’s the reason to watch.

On its twenty-fifth anniversary release, American Movie is a window into a forgotten era of outsider filmmaking.

There was no YouTube when it first appeared, no Project Greenlight or Kickstarter. Self-funded hits like The Blair Witch Project and Paranormal Activity were just peeping over the horizon. Back then, if you wanted to make your own movie, the most you could do was max out your cards and hit up your relatives (both of which Borchart did, and more). If all it took was passion and drive to make a movie, Coven would be Citizen Kane.

What you see instead is a guy doing everything short of setting himself on fire to bring a movie to life.

Was Coven a good movie? I’ll give my answer later, but see for yourself: it’s a special feature on this 4K Blu-ray edition and it’s easy to find on YouTube.

Was it worth it? That’s the tougher question.

Documentaries about troubled films usually fall into one of two categories: 1) madness produces genius (Hearts of Darkness, Burden of Dreams), and 2) madness produces more madness (Room Full of Spoons, about the making of The Room). The first kind produces a sense of horrified reverence—sure, Coppola gave Martin Sheen a heart attack, but how else do you get Apocalypse Now?—while the second kind is fueled by derision. It might be so-bad-it’s-good or so-bad-it’s-awful, but you’re still being invited to laugh at the poor slob who actually thinks his piece of shit is destined for the Criterion Collection.

I can’t say that American Movie falls into either category.

Mark Borchart is no Werner Herzog, but then again he’s no Tommy Wiseau. He might be overestimating his chances, but he’s not delusional. What he is instead is driven: by the need to be a person of substance, to escape his demons, to be someone his children and ex-girlfriend can admire. He is not the first person to decide that making a movie will fix all of that. It’s called American Movie but it might as well have been American Dream.

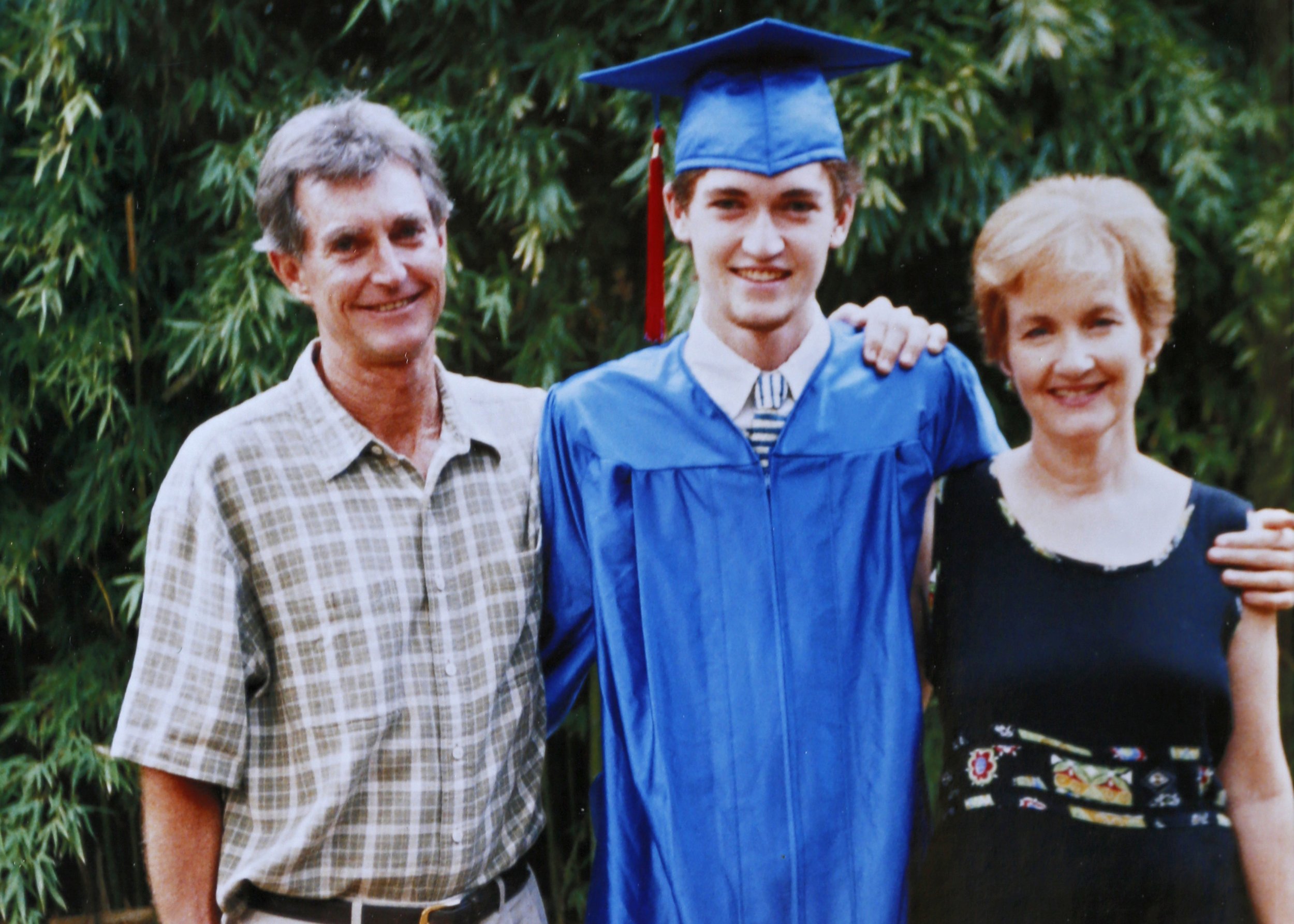

Borchart is very, very good at getting people around him to buy into his dreams. He cadges money out of his uncle Bill, who suffers from dementia and lives in a trailer park. His mother briefly becomes his camera operator. A friend and aspiring actor is willing to have his head repeatedly smashed into a kitchen cabinet door that’s supposed to break away but doesn’t.

And then there’s Mike Schank.

Mike is the Sancho Panza to Borchart’s Don Quixote. Think of Sam and Frodo, only living in rural Wisconsin with a lot more mullets and self-medicating. As teenagers they bonded over their love of vodka. Since then, Mike has traded booze for scratch cards (he figures that gambling is at least an addiction where you can occasionally win), but his trauma bonds with Mark Borchart are still in force. Mark is agitated, self-doubting, relentlessly self-obsessed—he has to be a filmmaker or die.

Mike is simply there.

He always seems to be just to the edge of the frame and slightly out of focus, being whatever Mark needs him to be in that particular moment: holding up a boom mike, finding gloves for witch costumes—they have to be brown gloves, Mark insists, even though the movie’s in black and white—showing up when other friends flake. It’s too easy to see Mike through Mark’s eyes, as a hanger-on or a factotum. At one point, Mark tries to get him pumped-up at the prospect of becoming a famous producer and Mike blandly muses that it might be a good way to meet girls. The truth is that most of Mike is beneath the waterline: during the few scenes where we catch him alone, it turns out he’s a soulful human and a wickedly talented classical guitarist.

This is why it’s hard to dismiss Borchart as the Ed Wood of northern Wisconsin, or Coven as his Plan 9 From Outer Space (though there are parallels to the self-confessional nature of Wood’s Glen or Glenda).

There is genuine feeling in (and between) these guys, which cancels out the urge to mock. Whatever Mark and Mike are going through, we’re going through it with them. During a Thanksgiving dinner, surrounded by his family and children, Mark wonders aloud if he might be a failure. Maybe he’s not meant to be a writer-director, just a guy who sweeps up at a mausoleum and hangs out the “We’re Closed” sign every day for mourners. His thought hangs in the air, unanswered, until one of his kids says what sounds like “shit.” Mark’s not mad that his kid might have said a four-letter word: he just wants to make sure that he really did hear a curse word, that he can trust his ears. As with many a visionary, self-doubt is always just a heartbeat away.

It would have been easy to let American Movie descend into cringe humor, but Chris Smith is determined to treat his subjects with compassion and respect. At one point, Mark’s ex-girlfriend notes that if he only accomplishes twenty-five per cent of what he aims for, it’ll still be more than what most people ever do. I don’t know many people who can get that kind of support from an ex. His family doesn’t always understand Mark but they stand with him. In the movie’s final crawl, we learn that Uncle Bill left Mark $50,000 so he could finally make his masterpiece, Northwestern.

The feature-length Northwestern never happened, but Borchart’s short film did. Coven (he insists on pronouncing it with a long O because he thinks rhyming it with “oven” sounds lame) is the story of a writer named “Mike” who is, it’s fair to say, consciously modeled on Borchart himself.

After a near-fatal combination of booze and pills, a friend encourages Mike to try an A.A.-like group that feels suspiciously like a cult. Mike begins to have delusional episodes that his fellow twelve-steppers are trying to kill him. Then it turns out that they really are trying to kill him, or at least smother him with toxic positivity. None of these are uncommon responses from someone attending their first Alcoholics Anonymous meeting, so I’d say Borchart is writing what he knows.

Thanks to American Movie, Coven has found a cult of its own, though it hasn’t exactly launched Mark Borchart to stardom.

It is not a bad movie. Its curse is that it’s almost good, which is much worse than being bad. A bad movie can be forgotten, but an almost-good movie demands more attention than it can ever reward. There are occasional flourishes in Coven—Borchart captures the gloominess of his native Wisconsin with unflinching honesty—but mostly it’s like watching a daredevil pilot trying to pull out of a tailspin.

Your heart wants it to work out but your head knows it won’t.

The performances are familiar to anyone who knows community theatre: everyone’s just a little too loud. The sets and costumes were clearly hashed together on a Saturday morning (take a close look at the hospital orderlies and you’ll see they’re wearing their drivers’ licenses instead of medical badges). The ending is what you get when you can’t afford to buy more film.

But honestly none of that matters.

American Movie isn’t about making a movie, it’s about wanting to make a movie—or rather, needing to make one. How many of us tried? There was a time when movie cameras were cheap enough, and audience expectations low enough, that it seemed like any one us could mine that lode. Steven Spielberg started out making movies in his backyard with a Super 8 camera. So did Mark Borchart and an endless line of would-be Spielbergs that we’ll never hear from because there was no Chris Smith to document their hopes and struggles.

Chris Smith specializes in dreamers who just missed their turn to success: Tiger King and his Fyre Festival documentary being recent examples. Because Smith shone a light on Mark Borchart and Mike Schank, we know Coven and what it took to get as far as they did.

It left me wondering just how many uncelebrated Borcharts there are in this world, desperately keeping their fragile dreams alive against the cold like penguins shielding their eggs. Struggling to achieve that twenty-five per cent of our ambitions and praying that it’s enough, knowing it’s not.

Maybe I’m one of them.

Maybe you are too.

Maybe there’s a little Mark Borchart in us all. Chris Smith’s gift is to let us look into that mirror without flinching from whatever we see.

Extras include commentary, deleted scenes and Coven film.

2 months ago

6

2 months ago

6

)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·