What history will record of Jimmy Carter was that he was the first U.S. president to broker peace between Israel and an Arab country. The 1979 peace treaty between the Jewish state and Egypt, the largest of its enemies, had been set in motion without him—but it would never have seen the finish line without Carter's determined push at Camp David. Without his belief in the human spirit, appeals to decency, and faith in a divine plan.

What cynics will say of Jimmy Carter is that while he managed to get Israel's Menachem Begin and Egypt's Anwar Sadat to sign on the dotted line, he did not set in motion the foundation for a wider Middle East peace. All one needs is to read the headlines today, 45 years down the road, to see that sometimes cynics have a point. Almost 50,000 people may have been killed in the mayhem of the past 15 months alone, and the Gaza war grinds on.

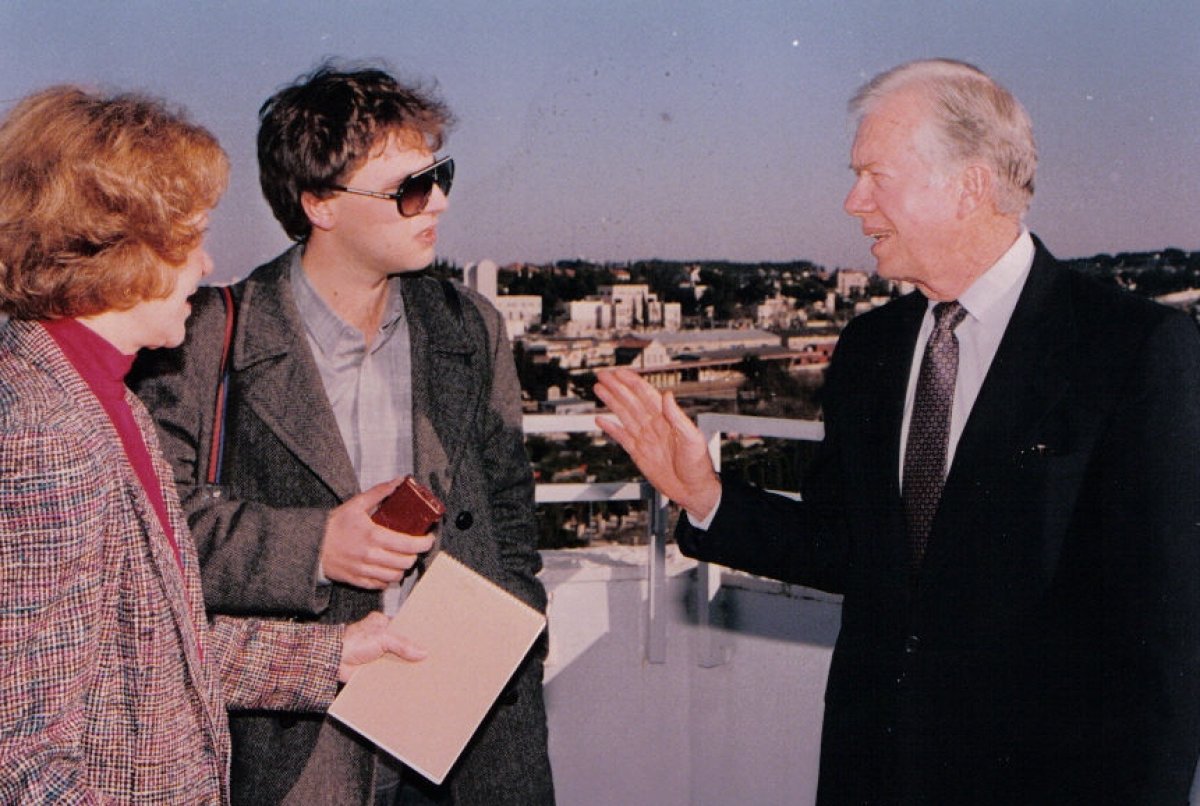

But what I will most remember of Jimmy Carter is his wife Rosalynn, glowering at us both on a balcony overlooking the walls of the Old City of Jerusalem, in March 1990. He had given a rookie AP reporter, trying to scam an interview, an entirely unreasonable amount of time. Her role, it was clear to me even at 26, was to keep her husband away from the reach of fools.

And this may touch upon the essence. He was so kind to me that day because he truly believed in people, as a calling and a way of life. Carter was not just a religious man but a profoundly moral one (the two do not always converge). His drive to bring together Begin and Sadat was based on these foundations, and to everyone's good fortune such things resonated then. "No more war," both subsequently pledged. All three won the Nobel Peace Prize.

Carter had hoped for even more. But his time in office was cut short by the turmoil of the Middle East. On Nov. 4, 1979, as his reelection campaign was gearing up, Iranian militants backed by the new theocracy there seized the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and took 52 Americans hostage. The standoff lasted 444 days, marked by a failed rescue attempt. The hostages were only released on Jan. 20, 1981, the day Ronald Reagan was inaugurated as president.

Carter devoted his post-presidency to peace as well, in the Middle East as elsewhere, and he was at it once again on the day I met him in 1990. Having recently met Syria's President Hafez Assad, he was trying to sell the Israelis on the idea that this heinous dictator might also be ready for peace.

I was attending a photo-op as a freelancer on behalf of AP in his room at the iconic King David Hotel, and as the camera folks were being hustled out I walked up to the white-haired old man, explaining that I could sure use some quotes so as to pretend I had an interview. "Let's have a word out on the balcony," he said. Looking horrified but resigned, as if she'd seen this many times before, was Rosalynn.

I asked how Assad might engage with Israel. Carter said that in a recent meeting he had found the Syrian dictator "ready to make peace, under the framework of an international conference." That was interesting! Assad needed the excuse of others in the room.

I pressed further, asking if Assad might agree to demilitarize the Golan Heights, which Israel had occupied in the 1967 war and had annexed. Israel returned the Sinai Peninsula, also occupied in that war, in exchange for peace with Egypt, and it had been demilitarized, a major Egyptian concession. Then again Israel never annexed the Sinai—complicated stuff. Carter hesitated: "I really can't say."

I began to ask more things, and the one-time peanut farmer, a consummate gentleman, was ready to reply. But Rosalynn finally stepped in, waving a notebook at him for some reason. "Jimmy, we really ought to go," she snapped. Carter tried to carry on, but under her glowering gaze seemed to consider his options briefly, and then dutifully complied.

I found myself reflecting upon the controversy stemming from Carter's 1976 interview with Playboy magazine in which he candidly admitted to having experienced "lust in my heart" for women other than his wife. I did not consider this a mystery and was glad I had refrained from investigating the matter in what I figure counts as my first major interview in an eventual 28-year career running around the world for the Associated Press.

Some will say that Carter was a naïve idealist, and that in his later years he was too critical of Israel for its continuing occupation of the West Bank. They'll argue that he underestimated the pure evil of jihadist nihilism, and they may certainly have a point. You can always quibble with great figures in history.

Others will deride his "crisis of confidence" speech on July 15, 1979, which I remember hearing in my parents' car. "The erosion of our confidence in the future is threatening to destroy the social and political fabric of America," he said, lamenting that selfishness was undermining the nation's character and warning that America's identity as a hopeful, united people was at risk. The speech was panned as defeatist, with critics dubbing it the "Malaise Speech"; I think it was clearly prescient, just four decades before its time.

Carter, who was president from 1977 to 1981, had achievements beyond Camp David. He negotiated the Panama Canal Treaties, transferring control of the canal to Panama. He normalized relations with China, paving the way for a new era in U.S.-China diplomacy. And he made human rights the cornerstone of American foreign policy, supporting dissidents in the Soviet bloc and challenging regimes that oppressed their people. But he'll be remembered for his successes (Camp David) and his failures (the Iran hostage crisis and the legacy of mayhem) in the Middle East.

As for Assad, in the subsequent decade he did negotiate with Israeli prime ministers Yitzhak Rabin, Benjamin Netanyahu (in his first term), and Ehud Barak, but a deal was never reached. Assad died in 2000 and was succeeded by a doltish-seeming son, Bashar, who's recently been in the news. Middle East peace remains, shall we say, elusive. Carter lived to see so much and yet so little: shifting alliances, moments of progress that always slip away, depths of depravity such as the one we see today.

He also lived to see Donald Trump occupy his former seat in the Oval Office—a surreal turn of events for a man whose moral compass defined his public life. Trump, it's fair to say, is the polar opposite: Everything to him is a transaction, and he sees morality as for the weak. But Trump may be more suited for the Middle East today: It is a time for bashing heads.

Carter's longevity is astonishing; he lived to 100, becoming the longest-living former president in U.S. history. It is equally astonishing that this supremely decent man did not succumb earlier, to a broken heart.

Dan Perry is the former Cairo-based Middle East editor and London-based Europe/Africa editor of the Associated Press, the former chairman of the Foreign Press Association in Jerusalem and the author of two books. Follow him at danperry.substack.com.

The views expressed in this article are the writer's own.

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/04/24/878/n/3019466/36c5693c662965c5d1ce91.72473705_.jpg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·