Warner Bros.

Robert Harmon’s The Hitcher is one of the greatest horror films of the 1980’s, full stop.

It’s also so much more.

A dark fairy tale; a thriller; a coming-of-age story; an urban legend; and at times even a rollicking action film The Hitcher is propelled across the screen with menace and bravado. Led by a pitch perfect performance from Rutger Hauer as the eponymous hitchhiker whose fascination with death and unexplainable prowess at killing make him one of the most terrifying antagonists in film history.

The Hitcher opens with a perfect example of what I call a “Hitchcockian predicament”: a situation where the main character does something that we all know we’re not supposed to do but in the moment we can understand and empathize with it.

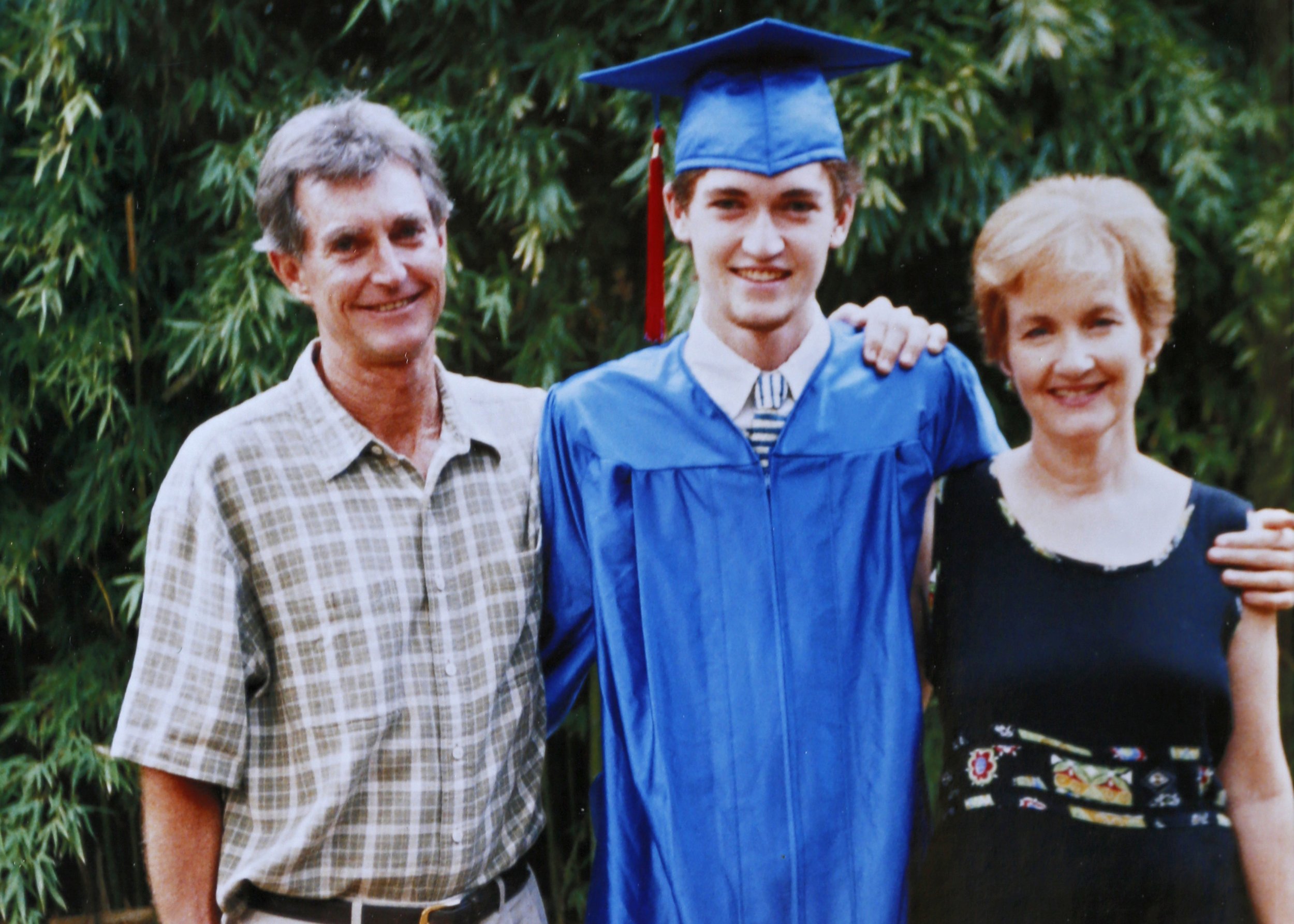

In this case, Jim (C. Thomas Howell) is taking a car across the country and has come to a kind of “dead zone” on a southwest highway. After nodding off nearly gets him in a head on collision with a tractor trailer, we can understand why he’s willing to pick up shadowy hitchhiker John Ryder (Hauer).

It is a decision he will instantly come to regret.

Ryder is psychotic and holds Jim at knifepoint, but Jim is able to dump him out of the car when he realizes he hasn’t shut his door all the way. ‘

What follows is a game of cat and mouse unlike any other in American cinema played out along a deserted stretch of disused road where Ryder is able to keep Jim dangling on the hook for almost the whole running time of the film, with Jim barely escaping by the skin of his teeth.

The Hitcher pulls off one of the most daring and difficult balancing acts in movies: it has an antagonist who is exactly where he needs to be at all times throughout the action of the film, without the film feeling cheap or sloppily written. The building intensity of the confrontation and sheer gravitas of Hauer’s performance as Ryder compel us to consider the Hitcher as a mystery rather than a character of convenience.

As good as the cat and mouse game of the film’s action is, what keeps The Hitcher legendary is how beneath the surface of the film there’s a fable, maybe even a myth about growing into manhood and about our capacity to handle the inevitability of death. When Jim swerves from the tractor trailer in the opening, he’s symbolically entered a kind of netherworld of disused Americana, patrolled by a devil in human guise who can find him anywhere.

This is well and good but as the action builds it becomes clear that what Ryder truly wants is for Jim to join into the process of taking life– he wants him to make some kind of arrangement with death.

It’s only after Ryder involves Jim’s love interest Nash (Jennifer Jason Leigh) in their escalating war that Jim can become proactive in his violence, and meet the devil on his own terms.

There is a sense, almost unique in horror films of this period, that the action and suspense meld with metaphorical underpinnings– that Jim slowly becomes conscious that Ryder is pushing him towards a kind of adulthood in the most sadistic and destructive way possible.

Extras include commentaries, a retro interview, and trailer.

What we’re left with is The Outsiders mixed with Halloween with a dash of Vanishing Point thrown in. As in the best Hitchcock films, the process of the film is the journey of the main character to become a hero, but here its tinged with a bittersweet inevitability about the prospects of death that Hitchcock would have been unable to use in the days of Hollywood censorship.

A wonderful thriller.

Highly recommended.

2 months ago

6

2 months ago

6

)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·