Health care has a workforce problem. Hospitals around the country are betting on high school students to be part of the solution.

In January, Bloomberg Philanthropies launched a $250 million initiative to create 10 health care-focused high schools around the country. Each high school is partnered with a nearby health system that has committed to creating job opportunities for graduates.

"America needs more healthcare workers, and we need a stronger, larger middle-class—and this is a way to help accomplish both goals," said Michael Bloomberg, founder of Bloomberg Philanthropies and Bloomberg L.P., in a January 17 news release.

Now, four of those high schools are wrapping up their first semesters. One of them—HEAL High School in Houston, Texas—has given Newsweek an inside look at its early challenges and successes.

HEAL is a partnership between Aldine Independent School District and Memorial Hermann Health System, a 17-hospital system spanning Houston and Southeast Texas. Aldine currently enrolls nearly 58,000 students, more than 91 percent of whom are economically disadvantaged. That means that nine in 10 students receive free lunch, Dr. Adrian Bustillos, the district's chief transformation officer, told Newsweek.

The area within Aldine's boundaries is a health care desert, according to Bustillos. Most of the district's students have had little exposure to the health care field outside of the occasional doctor's visit.

But that appears to be shifting, thanks to the $31 million grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies. On August 12, HEAL welcomed its inaugural class of approximately 150 freshmen. The school aims to reach 190 enrollees per year, amounting to 760 total students by 2028.

Students from outside Aldine are also welcome to apply, though partnering with this district was intentional, Dr. David Callender, president and CEO of Memorial Hermann, told Newsweek. The health system has been working to reach communities beyond its four walls, particularly those who struggle with non-medical drivers of health including lack of stable food supply, poor transportation and unsafe or insecure housing. These factors, also called social determinants of health, can lead to worsened health outcomes and even lower life expectancies.

"We know schools that serve those areas are a tremendous opportunity for us to make connections," Callender said. "The staff at the school help students better understand their health and how they can manage [it]—and in the process, introduce them to the concept of a health care career."

Health care is facing significant workforce shortages that are poised to worsen in the coming years. An August Mercer report projected that the U.S. will be short more than 100,000 health care workers by 2028.

"If we don't have enough people, it's pretty hard for us to deliver the care that we want to deliver, even if we're assisted by artificial intelligence or other technology," Callender said.

Since health care workers are in such high demand, students who enter the field are likely to enjoy high wages and job stability—and HEAL aims to help them get there.

Students accepted to the high school can choose from five pathways: nursing, medical imaging, pharmacy, health care business administration or physical and occupational rehabilitation. By graduation, they will have obtained not only a high school degree, but a professional certification that will allow them to apply for jobs in their chosen field (such as in pharmacy technician, phlebotomist or clinical medical assistant roles). Every student that completes the program will have a guaranteed priority interview at Memorial Hermann.

HEAL will also aid students who wish to receive a college education, Bustillos said. In addition to graduating with 15 to 24 transferable college credits, students will have the support of Memorial Hermann staff and mentors who can help them prepare for applications and interviews.

That support is especially valuable for Black and Hispanic students, who remain underrepresented in medical schools compared to their shares of the U.S. population, according to a 2023 study in JAMA Health Forum. Black and Hispanic students are less likely to have a parent with a higher education degree than their White peers and may have less access to the networks and "informal knowledge" to help navigate the application process, the study found. Medical schools value shadowing experiences and extracurriculars that can be difficult to access for Black and Hispanic students in under-resourced areas.

Once per month, HEAL students meet with their health system mentors in small groups. That personal connection could help dissolve barriers to higher health care education in the district, according to Bustillos. Nearly 75 percent of Aldine students are Hispanic and approximately 22 percent are African American, with over 84 percent of students considered "at-risk."

"We're going to build bridges to remove all obstacles to how students go into post-secondary options in the [health care] field," Bustillos said.

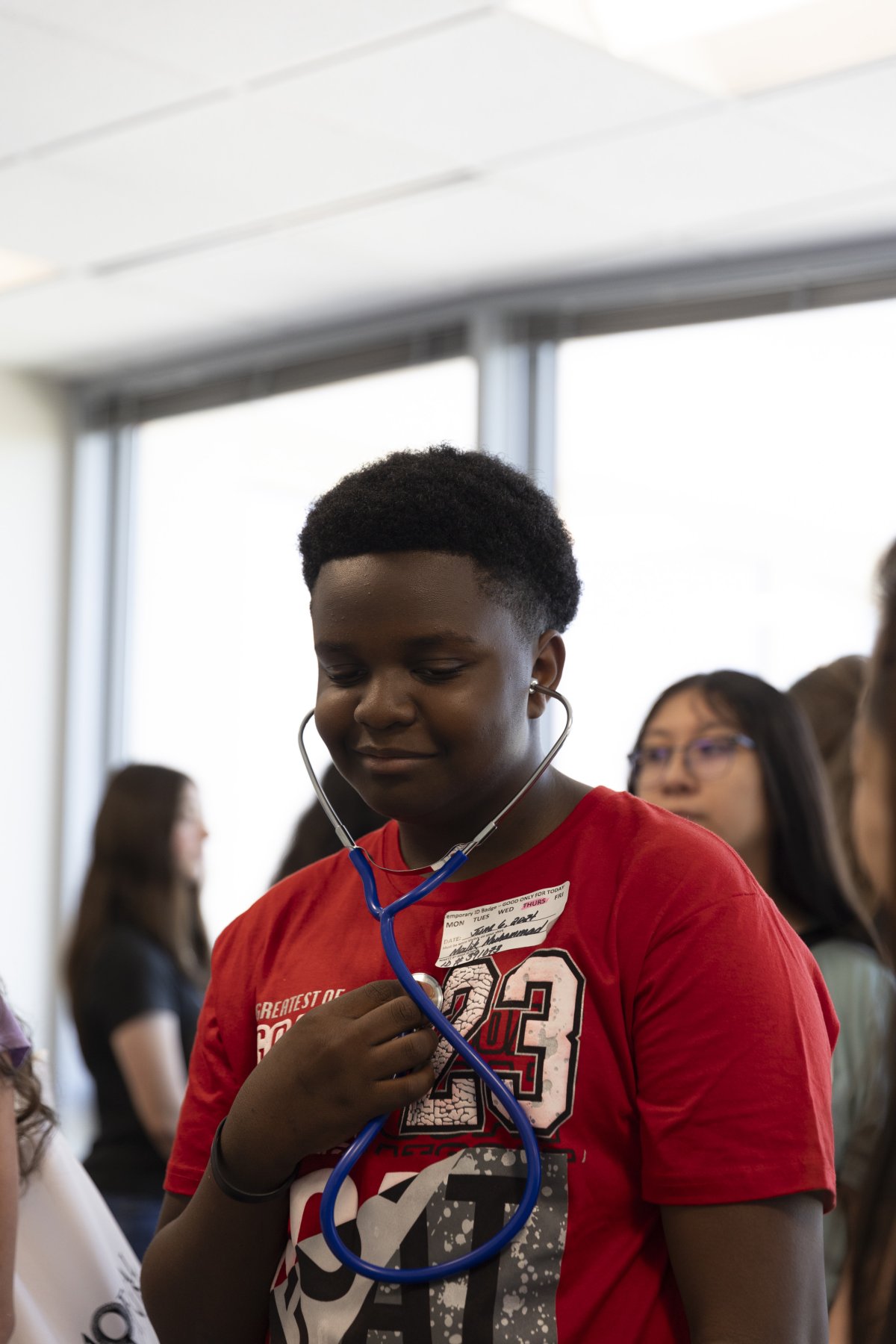

The transition from middle to high school can be shocking for any teen, but HEAL students have unique responsibilities on their shoulders, Yrayda Lopez-Silva, HEAL and student initiatives coordinator, told Newsweek. As the liaison between the high school and Memorial Hermann, Lopez-Silva has watched students bloom under pressure—especially after their first hospital visit. When students saw their classwork translated into the workplace setting, they looked at learning through a different lens.

"From there, they walked a little taller, took things a little more seriously," Lopez-Silva said. "You could sense the pride that they have in themselves."

Ricardo Flores—a baseball player with aspirations to become a sports medicine doctor—is wrapping up his first semester at HEAL. He starts the day in his "normal classes," like math and biology, then moves into health care classes, like medical terminology and principles of exercise.

Flores told Newsweek he enjoys the hands-on curriculum that, so far, has included CPR training and trips to the hospital. When the ninth-grader is on Memorial Hermann's campus, he catches glimpses of his potential.

Visiting the hospital "felt good," Flores said, "because I felt like that was going to be me in the future, so I really saw myself there."

Students receive more hands-on training as they move through the program. In ninth and 10th grade, students receive just over 30 hours of simulation training and mentorship each academic year, Callender said. By 11th and 12th grade, that instruction has more than doubled to 80 hours.

Currently, the high school is building simulation labs that will emulate the hospital rooms at Memorial Hermann. About $6 billion of grant funding has been allotted to the project, which will take up around 6,500 square feet of the high school, according to Callender.

When the labs are complete in the fall of 2025, students will be able to practice in faux medical-surgical suites and intensive care units, nursing stations and radiology suites. There will be a pretend pharmacy, equipped with the same inventory control systems and devices that real pharmacists use. Students will use virtual reality headsets, mannequins and other medical devices to practice skills without risk.

"The great thing about a simulation lab is you don't have to wait for an event or an occurrence to use as a teaching scenario," Callender said. "You can stage that."

HEAL hasn't been without its challenges, according to Brooke Martin, Aldine's executive director of career and technical education. The program is still in its infancy, so the first semester has been filled with continuous review.

For one, there are the scheduling constraints as administrators work to fit dual-credit opportunities, industry certificates and a regular high school diploma into a four-year curriculum. Since the curriculum is new, both Aldine and Memorial Hermann are paying close attention to students' engagement levels and pass rates.

Teachers and mentors are trying to strike a balance: pushing students to their full potential, yet encouraging them to enjoy the experience. The health care industry is already overwhelmed by burnout.

"We're challenging a group of kids here to mature a little bit faster [but] we don't want them to lose that high school experience," Martin said. "We don't want them to grow up too fast."

Martin describes the experience as flying the plane while building it—and writing the manual. "Every day is a challenge," she said. "It's not a bad challenge."

High school and health system leaders who spoke with Newsweek noted that over the first semester, students have changed not only professionally, but personally, becoming more confident and self-assured. For Martin, one moment stands out.

Students took part in a four-week orientation over the summer to help them acclimate to the program. Three weeks in, students were at Memorial Hermann Northeast Hospital to learn about bedside manner. A staff member pretended to be a patient as students practiced their conversation skills, then gave feedback and asked what each student enjoyed about the experience.

One student's reflection left staff members teary-eyed, Martin recalls.

"I talked to you," the student said, "and I didn't have a stutter."

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/04/24/878/n/3019466/36c5693c662965c5d1ce91.72473705_.jpg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·