When I became the head of the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Corrections (ODRC) in 2011, I strongly supported the death penalty. I knew it would be my job to carry out executions, and I accepted that role without hesitation. Seven years later, when I left the position, my views had forever changed. I came to understand that the death penalty causes great harm and drains significant resources, yet does not make us safer.

That is why I hope that before President Joe Biden leaves office, he commutes the sentences of all those on federal death row to life imprisonment without possibility of parole.

During my tenure as ODRC director, I personally oversaw 15 executions. Here is what that meant.

Fifteen times, I stood in a small room and ordered my staff to inject lethal chemicals into another human being, resulting in his death. Each of those executions left me with deep and lasting psychic wounds. They also took a heavy toll on my staff, even those who were less directly involved in the process. Correctional colleagues from other states have shared their own stories with me about experiencing long-term post-traumatic symptoms from participation in or proximity to executions.

Fifteen times, I met with victims' family members who chose to witness the execution. Those meetings were among the hardest in my long career. Some of the family members fervently believed the execution would bring them long-awaited justice, while others wanted the years of waiting to be over. I saw all of their faces as they left the viewing room, and I grew to doubt that continuing the cycle of violence and death brought any real peace.

Fifteen times, I told a man exactly when and how he would die, then handed him paperwork directing him to choose his final meal, specify the disposition of his meager belongings, and list the people he wanted to witness his death. I can say with complete confidence that not one of those 15 men were the same as they had been when they committed the crime decades before.

Fifteen times, I was tasked with finding the lethal chemicals to carry out the death penalty. This macabre task led me to some of the internet's most unscrupulous corners, and required me to expend vast resources—both human and monetary—to source and acquire the means of execution. Particularly at a time when correctional systems are struggling to recruit and retain qualified staff, there is no justification for continuing a policy that drains resources without improving public or prison safety.

The very purpose of a "corrections" department is to facilitate growth, transformation, and redemption. The death penalty is antithetical to that mission.

I spent almost 50 years working at every level of corrections, and in my experience, death row prisoners are indistinguishable from offenders serving life sentences. If anything sets the condemned apart, it is that they are likely to be poorer, darker skinned, or more mentally impaired; that they were assigned a worse trial lawyer; or that they committed a crime in a county with a more ambitious prosecutor. Death row prisoners are not uniquely dangerous within the prison community, and I've seen no evidence that having the death penalty deters crime at any level.

President Biden can address these problems in the federal system with the stroke of a pen. Commuting all federal death sentences to life will ensure that no federal employee faces the risk of lasting trauma due to executions. It will offer a measure of closure to the families of victims without taking another human life. It will honor the promise of redemption that lies within each of us. By using his clemency power to end federal death sentences, President Biden can grant mercy not only to the men on federal death row, but in a larger sense, to the corrections community and to all of us.

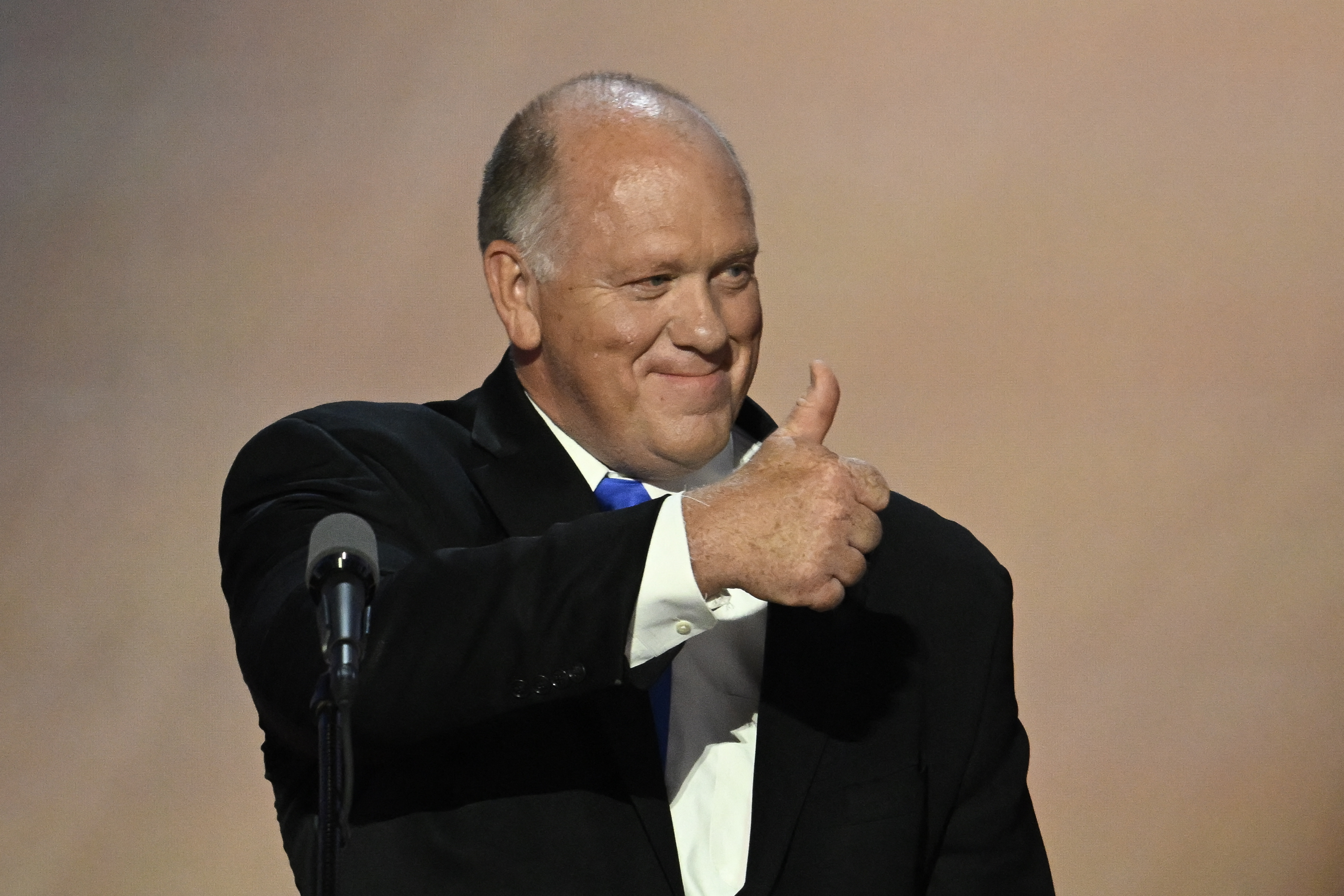

Gary Mohr served as the Director of the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction from 2011-2018 and has spent nearly 50 years working in corrections. After retiring, he served as president of the American Correctional Association. Gary continues to work on corrections-related issues across the country through his consulting business, Mohr Correctional Insight.

The views expressed in this article are the writer's own.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·