Greek military drills have pushed Russian sanctions-avoiding fuel swaps at sea to a new location, it has been reported.

Western-led measures on Russian energy exports that followed Vladimir Putin's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, were aimed at choking off revenues for Moscow's war effort and included a $60 cap on seaborne Russian oil.

Moscow has responded by creating a so-called "shadow fleet" of vessels whose ownership is reorganized to hide any Russian links, often through shell companies.

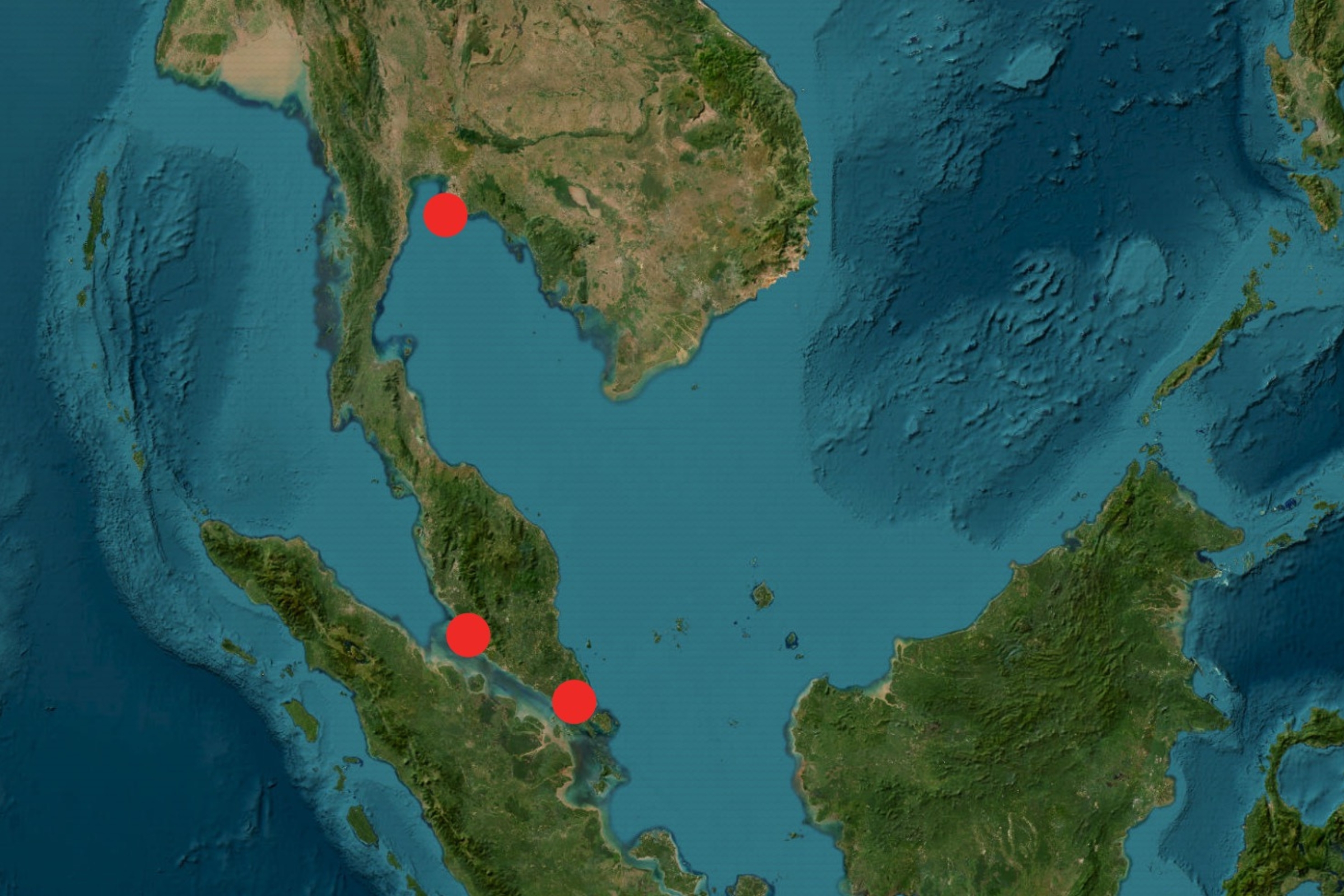

Russian energy exports are being shipped to countries in Asia and Africa that have not imposed sanctions. This process has been helped by ship-to-ship (STS) transfers which make it harder to trace the Russian origins of the oil products.

One prominent location for secret switches between ships was the Laconian Gulf in the southeastern Peloponnese in Greece, because of its proximity to Russian ports and the Suez Canal, which offers access to Asian markets.

But the transfers in this area reduced greatly after Greece issued notices for military exercises in the Laconian Gulf urging merchant vessels to avoid the area from May, according to Bloomberg, citing data from the firm Vortexa, which Newsweek has contacted for further comment.

The Greek drills have pushed Russian-trading tankers into new locations in the Mediterranean, the Red Sea and off West Africa.

Now, about one million barrels a month of diesel, fuel oil and other petroleum products are exchanged near the islands of Lesbos and Chios in the Aegean Sea, roughly 400 miles to the northeast, although transfers still also take place in the Laconian Gulf.

Yoruk Isik, head of the Bosphorus Observer consultancy, said the STS transfers in the waters off Lesbos were "a new development" and that when Greek authorities impose pressure, such as with drills, Russian operations are shifted elsewhere.

"That is a good place to hide because immediately to the north of Lesbos is a big anchorage area to transit the Dardanelles, so there are a lot of ships there," he told Newsweek. "Because of the geography, the sea is relatively calm."

He also pointed out the risks associated with these operations, highlighting the problems they could cause for Turkish authorities.

"It shows how dangerous these shadow fleet vessels are for Turkey because they are old vessels," he said. "The ship operations always come with risks—these are fly-by-night crews and tankers with a lack of insurance."

Russia's shadow fleet relies on vessels that are often older and frequently turn off their automatic identification system signals during transfers. Questions have been voiced over whether these ships have adequate insurance and environmental concerns have been raised in countries the ships sail past.

Isik said that the STS operations potentially put an area of Turkey that is popular with tourists in harm's way.

"No one knows if any of these ships are involved in an accident that any of the insurance is real and anyone will pay for the damage," he said. "There should be a joint Turkish-Greek effort to combat these ship-to-ship transfers."

Reuters reported in August that cargoes had been loaded on at least seven vessels in Russia's Black Sea ports of Taman and Tuapse over the previous two months for transshipment to other vessels in the northern Aegean.

Tracking data also shows that regular transfers are taking place off the Italian port of Augusta, according to the publication Trade Winds, which noted that the Greek military exercises would continue until March 2025.

There have been two near misses in the Danish Straits. In March 2024, a 15-year-old shadow tanker, the Andromeda Star, collided with an unnamed vessel near the northern tip of Jutland.

In May 2023, another shadow fleet tanker, Canis Power, loaded with Russian oil products lost engine power while passing through the Danish Straits and almost ran aground.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·